Agnes Denes at Socrates Sculpture Park

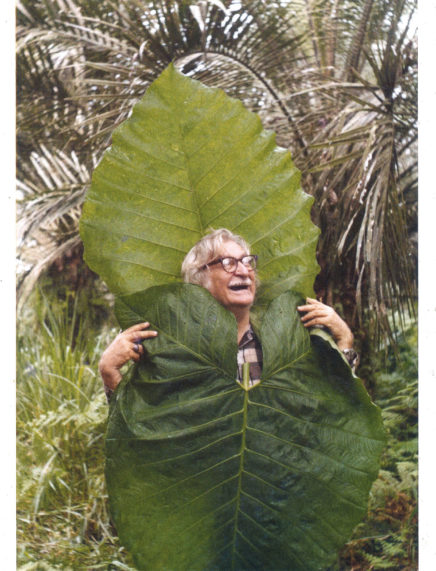

Agnes Denes, a major public art, land artist now in her eighties, still living downtown in New York City, has constructed a new work, a pyramidal structure called The Living Pyramid, for Socrates Sculpture Park, located in Astoria, Queens, across the East River from Manhattan. According to the press report, this work is the first major public piece done in the city since Denes’s Wheatfield—A Confrontation, created in May 1982. (The two-acre site consisted of wheat planted on landfill two blocks from Wall Street.) The Living Pyramid, done partly to honor David Rockefeller’s involvement with the arts and the environment during the month of his 100th birthday (June 2015), rises on the park’s landfill close to Hallets Cove; the northern tip of Roosevelt Island can be seen from here, as well as the Upper East Side of Manhattan. So Denes’s work is deeply connected to the city’s geography, as well as repeating some of the artist’s known interests in the persistence of nature in cities.

Although The Living Pyramid is less dramatic than Wheatfield, being a smaller work of art, its implications and visual statement are no less worthy. Thirty feet tall and thirty feet at the base, the sculpture curves slowly but surely into a single point. It consists of over fifty tiers of gray wood that build upward, supporting the growth of grasses and flowers. The tiers hold more than 340 planters boxes, in which eight types of flowers are found: sweet alyssum, calendula, gypsophila, marigolds, Durango outbacks, zinnias, impatiens, and geraniums. Three kinds of grasses are also grown: buffalo grass, annual rye, and silvertip wheat. The flowers, planted mostly on the lower tiers of the four-sided structure, add color to the green grasses, which Denes planted from the base to the tip of the sculpture. The Living Pyramid thus incorporates ecological diversity and demonstrates a commitment to protecting the environment in an otherwise heavily urban setting.

It is important to consider the public nature of The Living Pyramid in light of ongoing concerns about ecology, especially in major metropolises such as New York City. In 1982 Denes called her wheatfield “a confrontation,” which made sense given that she created a crop on land worth billions of dollars. The values of the wheat, known of course since archaic times as the staff of life, withstood, even if only for a short time, the exigencies of the value of the land on which it grew. As such, the wheat affirmed the primordial values of nature over the questionable ethics of savage capitalism. More than a mere gesture, Wheatfield set up an oppositional paradigm, one that, while limited in nature, challenged existing economic conditions quite literally on their own ground in New York’s financial district.

In contrast, The Living Pyramid is less directly antagonistic; we know soon off that it occurs partly in homage to a scion of the Rockefellers, one of the major banking families in America. It would seem that the time for open conflict is done with. Yet it is hard not to feel that Denes is asserting long-lasting, slightly unorthodox principles by including grasses and flowers in her work. What will we be left with as time goes on in a world whose resources are becoming more and more overwhelmed by demand? Central, even abiding, values come into play when people ask such a question. Part of the wisdom of The Living Pyramid is its willingness to allow nature to speak for itself, surely an important as well as necessary decision in New York City, where asphalt and concrete have the upper hand. By extension, too, Denes’s values can be expanded to include all urban areas, which serve both as the cultural address and tough environment of modern artists since modern times.

During the time I visited, classes were occurring on site at the park; a few women in swimsuits sunned themselves. The site itself is slightly unbecoming—Socrates Sculpture Park is perhaps better known for its intentions than its achievements up to now in landscape architecture. But this may change, and in fact, The Pyramidal Landscape will have something to do with such change: after the exhibition is over (it ends October 31, 2015), the 27,000 pounds of nutrient-rich topsoil will be distributed throughout the part—we remember that it is a five-acre area composed entirely of landfill, built upon two collapsed concrete piers. The soil distribution will help the parts of the site that need it most. Also, as director of communications Katie Denny Horowitz indicated in a letter, the wooden planter boxes will be set aside for community gardening. In consequences that demonstrate the principles of Beuysian social sculpture, The Living Pyramid comes full circle.

In summary, the changes occurring to The Living Pyramid after its exhibition is over parallel the changes that take place in nature itself—we move from construction to dissolution to construction again. There is a wisdom to this that may well take it beyond the politics that influence its origination. Denes’s efforts now have a context; the future of public art and land art is now being realized in the present tense. It is a movement based on the democratic efficacy, in both a moral and esthetic sense, of an art that speaks to as wide an audience as possible. The fact that anyone can see The Living Pyramid is outstanding; moreover, its dismantling recognizes that most culture today is impermanent. This does not mean it is of small value—quite the contrary, the piece gains in worth for its momentary resistance to forces, mostly human and economic in nature, that would deny its worth. It may well be we cannot ask more of contemporary art.

The Living Pyramid

By Agnes Denes

May 17, 2015 – August 30, 2015

Socrates Sculpture Park

32-01 Vernon Boulevard in Long Island City, NY 11106

www.socratessculpturepark.org and http://bit.ly/1im6giS

Socrates is open everyday, 10:00 AM to Sunset, free admission