Encounters in Hong Kong — Art Basel 2017

Art Basel Hong Kong’s Encounters is an exhibition of monumental works displayed throughout the unconventional context of a convention centre. This year, seventeen large sculptures and installations punctuated the long corridors of gallery booths with a range of artists, media and concepts. In the midst of a commercial art fair, it is refreshing to come across impressive works that articulate thoughtful statements about neoliberal capitalism, global and local concerns and also ideas around originality and value.

Li Jinghu’s Archaeology of the Present (Dongguan) (2017) is an installation which reframes an earlier work, White Clouds (2009). In this new work, Li has suspended reassembled lights used by factories into lines to produce an abstract formation of clouds displayed above a work composed of discarded mould fragments recouped from an assembly of rusted industrial moulds that were once used for the mass-production of toys. Archaeology of the Present (Dongguan) explores the emergence of Li’s hometown as a ‘factory of the world’ in the era of globalisation. Most of the factory workers in Dongguan moved away from fields in the countryside to take up work at the city factories in search of a way of supporting themselves. In Li’s piece, the clouds in the sky have been replaced by the florescent lights in the factory, drawing attention to the dislocation of the workers from their previous connection with nature. Below this, the installation of toy moulds evokes the material flux of the Pearl River Delta region. An area in Southern China where an immense volume of objects are manufactured and shipped worldwide, at rapid speed, causing this particular industry to quickly fall into obsolescence. The architectonic outline of the moulds’ display alludes to the cityscape of Dongguan, thus contributing to the artificial landscape Li has constructed here to comment on globalisation, industry, culture and the relationship of workers to nature.

Nearby, Pio Abad’s Not a Shield, But a Weapon (2016) appears curiously out of place. Abad’s work is laid out to mimic the displays of street vendors selling fake bags. Arranged in a gridded formation, clean white sheets are laid out to display 180 newly reproduced bespoke handbags. The bags are all identical, modelled after Margaret Thatcher’s Asprey purse, featured in a 1985 photograph of the former PM walking alongside US President Reagan. This work proposes a direct link between Margaret Thatcher’s neoliberal legacy and the history of the city of Marikina, Philippines where the ‘fakes’ were produced. Marikina, was formerly a city with a booming leather manufacturing industry, which has fallen into decline since the easing of trade restrictions in the early 1990s. Like Li’s work, Abad’s questions the relationship between globalisation, politics and industry.

Also exploring the impact of globalisation within a local context is a work by Gonkar Gyatso. Family Album (2016) is a sculptural installation that reveals the complexity of identity, particularly from a Tibetan cultural perspective. This larger than life installation is composed of seventeen of the artist’s family members who appear as cut-out figures atop a stage-like platform. The platform is framed by a long drape that references sources ranging from religious scroll paintings to propaganda. Gyatso’s work presents a story of the new Tibet, one that exists as a remote culture that is increasingly becoming part of a globalising world.

The cut-out figures are dressed for a variety of settings wearing work, traditional or holiday costumes. The variety of garments that these figures don can be seen as an outward symbol of how they navigate these various settings. However, the expressions and postures of these figures emphasise their individuality. Gyatso’s work considers the confrontation of globalisation and a mediatised society with local communities and identity. According to Gyatso, ‘At the intersection of representation and interpretation lies a deep and vast area that is so complex and at the same time very beautiful. If my work is ambiguous, it is, perhaps, because this I where I find myself.’ Formally, Gyatso’s work straddles the pictorial and the sculptural, further developing this sense of ambiguity.

Similarly, Dinh Q. Lê’s, The Deep Blue Sea (2017) is a photographic work, installed in an overwhelmingly sculptural manner. It is displayed as a cascading scroll installation that bears an abstracted image recalling ripples, waves and waterfalls. This work is composed of four appropriated images of the ongoing boat refugee crises in the Mediterranean Sea. To create each component, Lê stretched a single image across a 150-foot expanse, creating an arresting scale to scrutinize the significance of still frames and overturning Cartier-Bresson’s notion of the ‘precise moment.’ Instead, with his work, Lê argues for a fluid view of history that is permanently etched in our historical memory and asks viewers to experience the image as an abstract canvas upon which they are invited to project their own narratives and to use as an ‘aide-memoire’. Although this work uses recent history as its subject matter, it also echoes Lê’s personal history, when his family escaped Vietnam by boat in 1978.

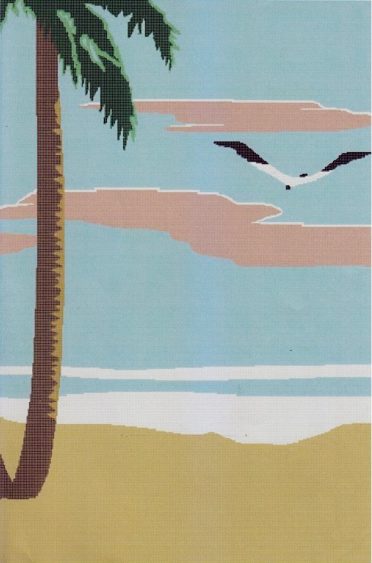

Wang Wei’s Slipping Mural 2 (2017) is a large-scale mural installed on the floor of the convention centre. This work develops from a series of works in which Wang has taken the Beijing Zoo’s animal enclosures as the starting point. Wang is interested in the zoo’s depiction of nature to mimic animals’ native habitats. Their enclosures act as framing devices that enable visitors to imagine a more naturalistic scene or perhaps more sinisterly, encourage the animals to feel more at home in these artificially constructed environments. Slipping Mural 2 is produced in mosaic tiles, portraying a beach scene with sand, palm trees and seagulls. Wang is interested in calling into question issues surrounding nature and artifice and the ability of architecture to physically and psychologically shape our environments. Throughout the course of Art Basel, visitors began to engage with the work, using it as a place to meet, sit, relax and chat.

In addition to this work, two monumental bamboo structures by Raheed Araeen and Rikrat Tiravanija also invited visitor participation.

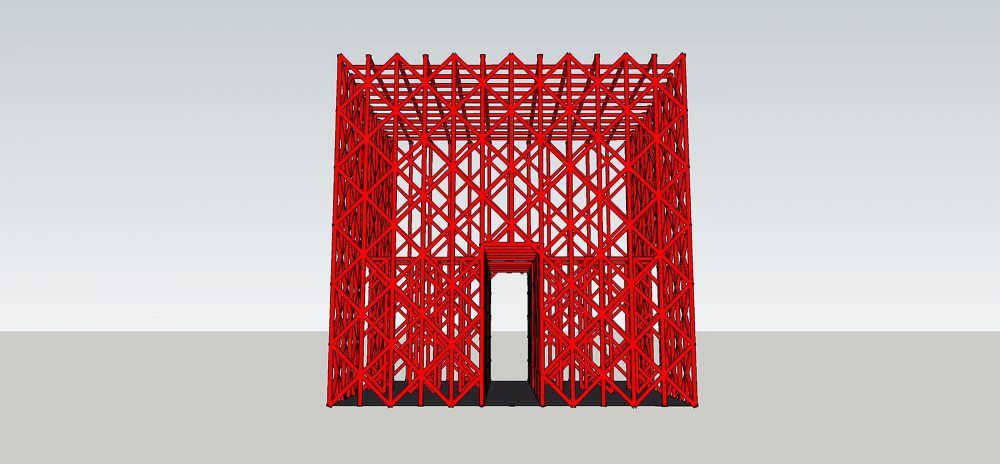

Rasheed Araeen’s House of Red Bamboo (2017) took the form of a painted scaffolding structure divided into a grid containing a passageway which visitors could traverse. Using the iconic lattice-rigged bamboo scaffolding found in the built environments of Hong Kong, this work immediately referenced its immediate surroundings. In addition to its utilitarian role as a construction material, bamboo is also often employed in Hong Kong to produce temporary public performance structures for the production of Chinese opera and festival stages.

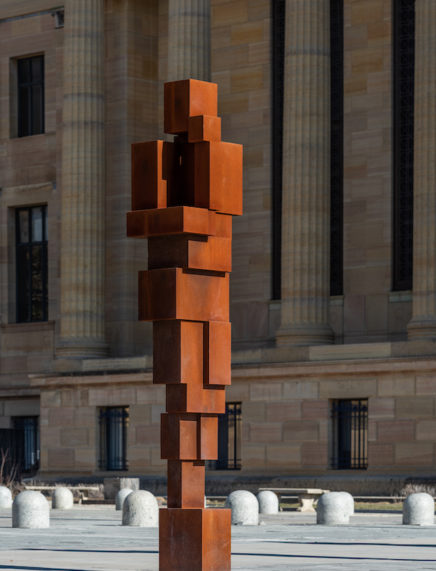

Rirkrit Tiravanija’s work untitled 2017 (no water no fire) (2017) is also built of traditionally-tied bamboo scaffolding, similar in scale to Araeen’s; however, the pathway through this work is a maze along which viewers encounter five versions of a 3D-printed bonsai tree set on bases inspired by Constantin Brâncusi’s wooden pedestals. This work weaves art historical references together with questions around technology and nature. Bonsai trees require persistent, thoughtful and delicate labour to disguise any signs of artificial intervention; for the viewer they represent the beauty of the human hand working in harmony with a fractal configuration of nature. This balance between natural form and human intervention was a balance Brâncusi constantly strove for in his work. With this in mind, Tiravanija’s untitled 2017 (no water no fire) invites viewers to enter it and to consider both technological singularity and the transience of nature.

These are just a selection of the many ambitious works that could be seen at this year’s Art Basel in Hong Kong. Other works featured in Encounters by artists Katharina Grosse, Joyce Ho, Hu Qingyan, Bingyi, Waqas Khan, Kimsooja, Alicja Kwade, Sanné Mestrom, Michael Parekowhai and Shen Shaomin are equally thoughtful, provocative and monumental.

Art Basel Hong Kong

29 – 31 march

Hong Kong

Convention & Exhibition Centre

1 Harbour Road

Wan Chai

Hong Kong, China