Lynda Benglis at Storm King

Active for more than half a century, Storm King functions as a major center for contemporary sculpture in a 500-acre, bucolic setting one hour north of New York City. With sited works by such well-known artists as George Rickey, Magdalena Abakanowicz, Mark di Suvero, and Zhang Huan, Storm King serves as a testing ground for some of the most creative spirits of our time. Always a destination of pastoral beauty, the grounds harbor an anthology of international artists, whose mission here is to communicate a vision, most often abstract, in which the imagination of current or late artists is subsumed within the rolling hills and open meadows of the sculpture center. I can think of no other place in America where there has been such a successful interaction between the landscape and the creativity of artists whose work is usually seen in the concrete spaces of the city, where accomplishment is now filtered through careerist ambition and hard money.

The romance of nature and its contextualization of contemporary sculpture is not without its difficulties. Nature can be so seductive in its own right, sometimes it proves hard to focus on the work alone! This does not mean that the art is slighted or overwhelmed by trees and fields; instead, it can be suggested that the role of a public, georgic site devoted to cultural enterprise is to create an environs within which art can be fully appreciated—without the distractions of urban life. Now that the market has more or less completely taken over the careers of good and great sculptors, it seems that a cash-neutral showing space becomes more and more important. Given the financial stresses of a city like New York, this can no longer be done easily, even if New York retains its primacy as a place to exhibit. By contrast, and in contradistinction, a rural setting can be understood not merely as a merely beautiful context for the display of sculpture; its distance from areas of commerce enable art to be seen relatively objectively, without the scrim of finance intervening between the work and the viewer.

The role of public art now has a small contemporary history, although artists have informed me that it remains highly difficult, if not impossible, to live from such work alone. Yet the idea persists as a healthy antidote to an entirely private, money-driven understanding of what art can do. Lynda Benglis’s fountain sculptures have been placed nearby the house that serves as a visitor center and gallery space; they are marvelous examples of a wildly creative vision the artist has been developing for decades. Additionally, and importantly, these works would function not only in the green landscape provided by Storm King; they would also do well in urban settings, in which water-based art might serve as a place for city dwellers and tourists to gather, taking enjoyment in the mix of anti-formalist art and water that Benglis has done so well to combine in this show.

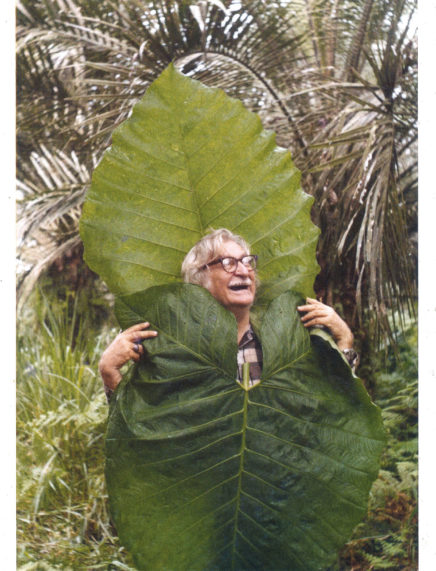

Benglis has always been a free-form artist, as these sculptures suggest. She is also infamous for her picture, nude and wielding an outsize artificial phallus from her crotch, in the November 1974 issue of Artforum. Although the image was criticized by feminists as an attention-grabbing device, the incident emphasizes the artist’s willingness to take risks—not only in art but also in life. This stance is very American and likely will have little to do with the actual visual achievement Benglis has accomplished. But, at the same time, Benglis’s erotic exuberance exists throughout her career, in the work itself. Her life as an artist presents an outlook different from the one we traditionally expected from a female life in art, coming as it does from a time of sexual experiment and openness. Interestingly, Benglis has been able to create a body of work that does justice to a sensual—an overtly sexual—vision of the world, one in which the desire to merge, erotically and emotionally, finds a real place in today’s theater of visual art.

Pink Ladies (2014), made of cast pigmented polyurethane and bronze, consists of three vividly pink-colored verticals, each of them composed of several cones from which the water drops from one container to the next. The color comes from a kite Benglis saw aloft while in Ahmedabad, India; in the fall of 1979, she took part in a residency there with the Sarabhai family and stayed six weeks. Since then, she has visited India on a continuing basis. The bright pink hue contrasts with the grays and browns of the house behind the sculpture, as well as with the deep greens of the grass and foliage. Like all fountains, Pink Ladies serves as a place to meet in addition to being an outstanding sculpture in its own right.

North South East West (1988/2009/2014-15), composed of bronze and steel, were constructed by Benglis pouring polyester foam over a large ceramic Ming pot extended with a wire support. The consequent forms, which mimic oceanic waves or the slow, rolling movement of lava, or insects of monstrous size, are a combination of conscious intent and the deliberate freedom allowed in the fabricating process, which is complex and requires other people besides the artist herself. At first, each of the four elements were identical, but then, according to press notes, Benglis reworked three, adding bronze elements to their exterior. The fourth element, East, has remained intact. Here something quite sinister is felt in these hulking forms which rise up as if to attack an invisible prey. Benglis has always been interested in a formalism that resolutely stays inchoate—an anti-formal formalism. This work embodies such an intent.

The trio of identical, 25-foot-high cast bronze sculptures are individually named Bounty, Amber Waves, and Fruited Plane (2014); these titles come from the famous anthem “America the Beautiful,” which of course is famous for its celebration of the natural abundance and beauty of the United States. The columns of cones rise up against the hills surrounding the open field in which they stand; the diameter of the pool they occupy is relatively small but nevertheless serves as a water setting for the three works of art. Crescendo (1983-84/2014-15) looks a lot like the forms of North South East West; here two hovering forms rise up out of the fountain, although Benglis indicates that they have to do with crustaceans and marine life: a porpoise momentarily jumping out of the sea. This work too results from addition; the artist poured polyurethane foam onto a bronze fountain called The Wave of the World (1983-84), originally installed in the 1982 World’s Fair in New Orleans.

The most recent work by Benglis shown here, Hills and Clouds (2014), is not a fountain; rather it is a heap—there is no other way of describing it—of poured polyurethane supported by a stainless-steel infrastructure. Phosphorescence lights up upper forms and some of the lower ones; Benglis made her first piece using phosphorescence in 1971. She remains interested in it as a natural phenomenon, in caves or in the sea. In this piece in particular, she says she wanted to develop the feeling of something rising upward, as opposed to being tethered to earth. At the same time, the flowing threads of the hummock-shaped swellings making up the sculpture indicate the long tendrils of moss on oak trees in Louisiana, where Benglis was born. The work is a triumph of inchoate nature.

Benglis is clearly an important artist, one of the most necessary sculptors of her generation. Her mixture of ebullience and humor is more or less without precedent; she has constructed an esthetic life from work that eschews high formalism. In this way she embodies the rebellion of a generation that worked out a kind of counter-culture, in which desire and a general antagonism toward the hierarchy of form merged in a boisterous denial of so-called “serious” art. This does not mean that Benglis has rejected culture—far from it. Instead, her lyric vision celebrates impulse and an originality of shapes that are closer to content than to formal artifice. In the long run, Benglis proves that it doesn’t matter what one’s origins are, so long as the work conveys energy and high standards. This is an important show.

Lynda Benglis: Water Sources

May 16 – November 8, 2015

Storm King Art Center

1 Museum Rd, New Windsor, NY 12553, USA

benglis.stormking.org