Ai Weiwei:

Good Fences Make Good Neighbors

Public art’s greatest strength—its accessibility—is also its largest weakness. We are living in a time when contemporary art has been considerably dumbed down—presumably for the not-so-hidden edification of the masses. But anyone who has made his way through the subway stations of New York City knows that visual art in a public context usually is fleetingly contemplated; moreover, the work often leaves much to desire in its earnest but casual, sometimes inexpert facture. In America, Maya Lin’s Vietnam memorial is often cited as one of the best public sites we now have, yet even that work raises questions. There is a conflict between its detached modernity as public art and the grand pathos of what it remembers—the tens of thousands of names cut into stone end up feeling more impersonal than moving. Often, too, public art can feel didactic—an experience readers in the subway confront when they read a poem put up by the Poetry Society of America, which, to be sure, goes to considerable lengths to make its choice easy to read and understand, even if the genre remains more or less intolerable for most riders. And many in the New York art world remember Chinese conceptual artist Xu Bing’s dictum “Art for the people,” put up as a banner hanging from the façade of the Museum of Modern Art in 1999. The Chinese, like the Americans, worry about those removed from cultivation; public works attempt to address the problem, but often fail because art has become so specialized an endeavor. Nonetheless, public art cannot be simply dismissed—its possibilities are endless—even if it rarely lives up to its potential, and the money made by the artist is poor to nonexistent.

The real question occupying the public artist is the question of audience. What should the poet do if there is no one to read his poetry? What should the artist do if no one pays attention to his work? What happens when the public is not engaged? There is just so much work the artist can take on before it becomes clear that his efforts remain marginalized and neglected, even to the point of being ignored. We can deplore the situation and call for change, but our time’s lingua franca is popular culture, not a category of art known for its grace or intellectual acuity. Consequently, subtlety goes by the wayside, in favor of a shallow literalism that means well but accomplishes little in its attempt to convey fine art to common people. The situation becomes worse when an artist tries to establish an awareness of history or promote a political point of view—usually the reaction is negligible. The causes behind the lack of a response are varied and complex. Public and political art must do a number of things to succeed: it must get the attention of as many people as possible; it must please or capture the eye of the viewer; and it must communicate values with social implications. In light of contemporary culture, with its reliance on—more accurately, its addiction to—mass technologies such as television and the computer, working relations between the artist and a general audience seems troublesome at best.

Those artists attempting to engage viewers in a conversation that would bridge the gap in thinking between people who are involved with culture and people who are indifferent to culture seem to have failed. The situation mirrors Marxist explanations of social problems, which accurately describe current circumstances—mass movements of impoverished people, the loss of jobs to technology, the turn to the right by workers—but has little to offer in terms of a solution. In a similar fashion, contemporary art may well expose the extent of our cultural poverty, but it is often unable to connect with people not immersed in the field. Today’s art is debased by its ironic use of popular culture—but popular culture remains necessary because it is the only currency we share. As a result, art trivializes itself by wanting to capture an audience with terms whose elevation is minimal. But it also may be true that fine art never truly spoke to common people; while America’s democratization of art in the last four decades has widened its audience, it has done so by repudiating high culture. There is a good example of this in the work of the British duo Gilbert and George, who declared that they wanted to make art that would be immediately understandable to everyone, no matter their class or education. But in America, the problem is compounded by a long-standing populist dislike of intellectual culture, which is seen as both arrogant and subversive. Populism in art is deeply embedded in our society. In recent years, art activities have often been conceptual, which has made art even more complex and, as a result, marginalized. But most recently, the drive to simplify in art has been supported across lines of class and education. At the same time, federal funding for art efforts is nil.

I have been talking generally about the American situation, but this article is meant to accommodate and clarify the New York project of Mainland Chinese conceptual artist Ai Weiwei’s project. His installation of sculptures and banners here in New York is meant to bring attention to the worldwide crisis in the movement of refugees. Ai Weiwei has been publicly prominent e for a decade. He knows America well, having studied at the Parsons School of Design and the Art Students League while living in America from 1981 to 1993. During this period, he became friends with the poet Allen Ginsberg. But in 1993 he returned to China to take care of his ailing father. Once Ai Weiwei returned to China, he engaged in a series of politically motivated activities, often occasioned by government ineptitude or repression. These actions resulted in the artist being arrested in April 2011 on charges of tax evasion—a governmental charge that was not without cause, but which made him world famous. In fact, the artist had been harassed for some time–two years earlier, in 2009, Ai Weiwei was beaten up by Chinese police in Chengdu, occasioning emergency brain surgery in Germany.

With world-wide media focusing attention on him, Ai WeiWei has become a symbol of humanitarian liberalism, which his current New York City project would seem to support. Entitled Good Fences Make Good Neighbors, which is a quotation taken from a poem by Robert Frost, the project entails art placed in three hundred locations throughout the five boroughs of New York City; the art includes major sculptural installations—including one under the arch in Washington Square Park; and another, in front of the southeast entrance to Central Park—as well as posters at bus stops and banners on light poles. This undertaking has consolidated Ai Weiwei as a major public figure in art worldwide. But the artist has been well known for some time; thus, the situation is more complex than it seems. Ai Weiwei has consistently sought the limelight as an artist, although the attention given to him is based more on his political actions than his creativity. His political activism, at least in China, is personal; his father was a well-known poet who lost favor with Mao, who had him and his family exiled to the provinces. This experience constitutes at least part of Ai Weiwei’s motivation. Because he has had his own experience of banishment, he is clearly capable of identifying with the plight of people in a similar situation worldwide.

One hardly dares to criticize so humanitarian a project, but perhaps it can be said that Good Fences invests more energy in its social program than in artistic achievement. Public art remains problematic as art; its ability to communicate visual pleasure can seem limited, in part because the artwork has to convey a message that usually is more important than the work’s visual efficacy. How could it be otherwise? The image must convey its point of view with a minimum of embellishment, which otherwise might direct the audience’s attention away from its content. As a result, many artists are hampered by the historical or political requirements of their theme. Even if we are sympathetic and substantially agree with the artwork’s political content, we often feel distant from the simplicity of the image’s transmission. In the case of Ai Weiwei, the motive is transparent: the plight of the refugee worldwide. Who would disagree with the nobility of the sentiment? The hardship of the refugee cannot be turned aside. But the sympathy cannot locate a responsible monster as the antagonists are anonymous—or too numerous to contemplate.

Because Ai Weiwei’s undertaking has a priori approval, its artistic effectiveness is oddly limited by the good will it is seeking to build. The support is already there. The point being made—the necessity for sympathetic treatment of the refugee—is a self-evident truism. In consequence, the issue becomes slack as art because there is no tension—no visible hostility between the victim and the perpetrator, who remains more or less anonymous. It might even be said that, as a result of lost relations between the injured party and the person(s) responsible, the project veers toward sentiment. Principle becomes secondary in the face of a feel-good situation that is likely unable to effect actual change. Surely Ai Weiwei, a highly intelligent artist and political gadfly, must know this. Does the project’s implications suggest that Ai Weiwei is muddled in his thinking? Or does the public art genre inevitably fail because of the gap between public art’s motives and its effects? (There are exceptions: John Heartfield’s photomontages present savage ironies, directed toward Hitler and the rise of the Nazis during the years before the Second World War.)

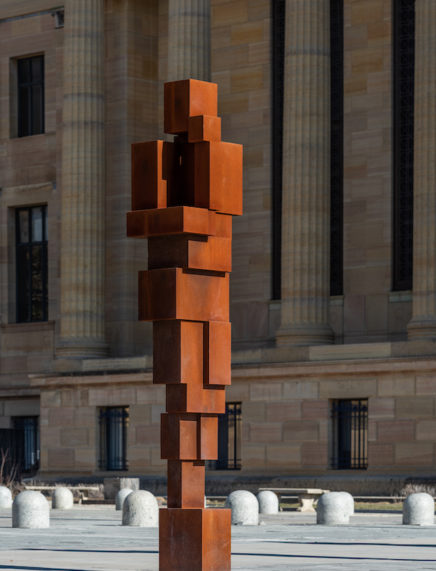

Ai Weiwei’s undertaking does in fact work. His steel cages and photographic images of refugees possess genuine pathos. Moreover, they are capable of lasting in his audience’s thoughts. But, inevitably, the poetry of the works fall slightly short; the art cannot compete with the reality of the suffering it is trying depict. I am not dismissing in any way Ai Weiwei’s program. We know that it is true suffering’s representation has never equaled the experiences that engendered it. But art has been capable of duplicating experience. It is also true that even if the visual gesture is forceful and accurate, most of the time real change is not brought about. As a result, a disquieting romanticism enters into the dialogue between art and viewer. In Washington Square Park, Ai Weiwei put up Arch (2017), a silver cage whose overall shape mimics the shape of the vault it stands under; additionally, a silhouette of two people forms a tunnel that has been cut into the cage. Lined with stainless steel, it allows visitors to pass through the enclosure. As a re-enactment of the refugee experience, it literalizes the event. The problem, though, is that our participation is voluntary—not brought about by force.

Inevitably in an undertaking like Ai Weiwei’s, there is a gap. The breach occurring between his project and actual exile cannot be spanned. Those constrained by barbed wire and those who enjoy freedom of passage are living two very different lives. In the southeast entrance to Central Park, Ai Weiwei has installed Gilded Cage (2017), which is a tall, circular gold structure, with an entrance for pedestrians. The structure has been painted gold, everywhere the color of luxury, and one remembers that President Trump’s apartment, an exercise in deliberate excess, is only blocks away. Gilded Cage may be telling us how the millions of illegal aliens in New York are in thrall to those who have little or no understanding of their position. It useless to belabor the point—an ethical response to suffering often remains a predicament without a solution. Because art is an activity often supported by money, it supposedly works within a more just society, in which these problems are not supposed to exist—at least in theory!

The criticism I offer may be too severe. Ai Weiwei is in fact a very gifted architect; the Three Shadows Photography Center, established in 2007 by noted photographer Rong Rong, was designed by him. The museum is a compelling, asymmetrical bullding that functions as effectively as sculpture as it does as architecture. The structures put up throughout New York City by the artist stand out as building or landscape design; in particular the Circle Fence (2017), surrounding the Unisphere in Flushing Meadows Park in Queens, succeeds both as a compelling example of playful art and a low-slung resting place for visitors. The fence, made with nets of rope attached to black bars, encompasses the Unisphere, a steel globe 120 feet in diameter created for the 1964-65 World’s Fair. No doubt the worldwide nature of the Fair was not lost on Ai Weiwei, whose ambitious installations throughout ethnic neighborhoods in New York attempt to reach many different kinds of people. Circle Fence is a striking work of art, but one might wonder if the people interacting with the work duly direct their thoughts to the tragic lives of those that gave rise to it. We cannot always think seriously about history, especially in the parks, where people are meant to enjoy themselves. So the theme of the art may be lost on the viewer

There is no answer to the social problems that cause the flight of refugees, and art has never been in a position to bring about actual, or enduring, change. Protest have been consigned to the margins. And it looks like artists are content to take symbolic action alone. Perhaps allegory is all art is presently capable of. But we can hope for more. A new level of commitment is needed. If art never did play a role effecting change, it still can elevate its meaning to the point where a metaphorical reality replaces a literal one. Doing so may lessen the specificity of the point being made, but something else is gained: a sense of real commitment, based on imaginative originality, rather than a tired rhetoric. This might lead to action as well as good feeling. Ai Weiwei’s global message is accurate and genuine, but it puts its trust in good will, which may not be sufficient in addressing the problems of refugees. This has nothing to do with the artist’s skill or good will; rather, it has to do with art’s inability to build monuments greater than castles in the air. In truth, the problem has been apparent as long as public art has been made; but its longevity does not stop our wish to make art more permanent—and more socially effective—than it has been.

Ai Weiwei: Good Fences Make Good Neighbors

Oct 12, 2017 – Feb 11, 2018

> interactive map