Carmen Herrera: Estructuras Momumentales

at City Hall Park (New York)

Carmen Herrera is now 104 years old. She is receiving, at long last, the attention she deserves. Originally from Cuba, the artist made her way to New York in the mid-1950s, where her work did not catch the attention of the art world, in part because Herrera was a woman from Cuba, in a time when both attributes made her an outsider, and in part because she was not actively seeking a visible career. But now her time has arrived, and in a major fashion, no doubt because of her full-floor show at the Whitney Museum a couple of years ago that brought widespread attention to her accomplishments. Primarily a painter, Herrera also makes sculptures, as this excellent show at City Hall Park demonstrates. It may be argued that the artist’s sensibility remains primarily painterly in this body of work, which consists of brightly colored, minimalist-shaped aluminum sculptures painted simple, single colors such as red or yellow. The art works remarkably well in a public context, in part because it offers no cultural history–only the pleasing appearance of geometric forms that remain in the visitor’s mind because of their formal immediacy and well-placed installation. In fact, Herrera’s art goes back a long way in the now-venerable history of modernism, and her output has, from the start, shown considerable efficacy and sophistication. Moreover, her geometric style has never gone out of favor in New York, taken as we are here by the hard-edge street corners and tall buildings that act as a frame for Herrera’s show, even downtown (above Wall Street), where the buildings do not regularly attain the height of skyscrapers in midtown.

City Hall Park surrounds the Mayor’s place of government, and is only a few hundred yards away from the walk across the wooden thoroughfare on the Brooklyn Bridge toward Brooklyn. While the park is not exactly a destination spot for tourists, it is also true that it receives many passersby–usually those making the pilgrimage across the lower end of the East River to Brooklyn Heights. What better place to install Herrera’s show than here, not terribly far from her studio in Chelsea? The sculptures, established in sites among shrubbery or confronting the city viewers making their way through the park’s expanse, argue for a continuing formalist reading of art in an urban area. Our response to the work is in contrast to most contemporary art efforts, which have been increasingly taken over by political remonstrance. New York has always been a great incubator for formalist abstraction, and it continues as a place where artists making work in this manner develop and grow. While the design of these pieces goes back considerably into the past of Herrera’s career, this hardly means she is entrenched, nor does the works’ place in Herrera’s personal art history undermine the essential immediacy of our experience of the art. The question is whether such simplified forms can sustain extended artistic interest over time, that is, into the future. My feeling is that the gestalt of Herrera’s sculpture is well-defined enough and original enough to provide her audience with a lasting impression–one in which the experience of the work is deepened by its placement in a public environment. This is exactly what public art is supposed to do.

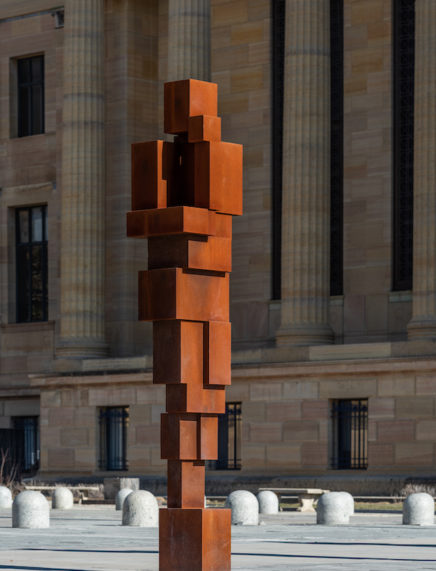

As for the sculptures, they are elegant three-dimensional paintings that tend to emphasize a frontal orientation, a positioning perhaps made necessary by the Public Art Fund’s need to place them effectively in the grounds, where small patches of grass, park benches, and pedestrian traffic all serve as physical constraints. Angulo Rojo (2017), a red triangle with its base missing, is just over ten feet high. It sits on a concrete pedestal in the middle of the park, dominating its site and the space around it in a forceful manner. Its bright red exterior surface acts as a magnet for the eye, in a way that emphasizes its nearly architectural energies. In many of Herrera’s works, paintings as well as sculptures, the geometry is not purely expressed; slight angles and incomplete edges force the work–and us–toward a perception of idiosyncrasy, in which the off-cuts of the image make it more profoundly interesting as art.

Very good art, geometric abstraction especially, tends to rely on a technical eccentricity whose effects sabotage our expectations of formal unity. This is a visual subversion that is not without public consequences, especially in the realm of public art, which one might reasonably assume carries political, as well as social or formal meaning. It is impossible to definitively associate abstraction with a political stance, although the Russian constructivist style was closely associated with the Soviet Revolution. But that is gone now, and we can only weakly comment on the now-familiar radicalism of a former particular art manner. Herrera is inevitably participating in a language that is politically neutral, although this may not have always been the case. Sadly, we find ourselves actively addressing the shape and form and color and surface of abstract work whose meaningfulness on a social level was far greater than it is now.

But even if we resort primarily to reading the work esthetically, the results are elegant and wonderfully intricate. Despite the seeming simplicity of the sculpture’s gestalt, the dark green color covering the sculpture gives the work a serious, nearly a solemn, aura. One hesitates to assign too much emotional perception to such resolutely nonobjective art, yet it can also be said that is all we can do, given that human feeling is not directly portrayed in the works. Untitled Estructura Red (1962/2018), a wonderful interlocking sculptural work, in which the lower part has an arm that rises up into a larger element that frames it, shows us how satisfying the interaction of simple geometric forms can be. Herrera consistently uses the Spanish word for “structures” to describe her efforts, and the concept behind it emphasizes the essentially impersonal nature of her art–for example, we must read about the unhappy circumstances of the fatal illness of her artist’s brother, for without the written information we are unable to infer the tragic situation animating the work of art.

But perhaps concern about how much information we should have in regard to these remarkable works of art is not as important as it would seem at first. Abstraction can in fact be tied to human concerns and situations, but primarily it is about itself–its own paradigms of shape and color and overall composition. It is inevitable that modernism, now more than a century old, would have invited us to consider these properties as needing investigation in their own right. But it is just as inevitable that abstraction’s audience, needing to humanize the inhuman, would explore the ways in which nonobjective art might be made figurative, in both a formal and a thematic sense. Still, given that Herrera’s art is so very remote from the human as we usually conceive it, it makes sense to read it in purely formal terms. In the works described in this review, the visual interest regularly results from slight changes in our expectations of the regular or the conventional imposed on geometrical form. These slight crevasses separating one part of the work from the other, along with the way components balance and contain different elements of the same work, make it clear that Herrera regularly generates interest from subtleties that come from a specialized regard for abstract form.

In a city in which statues of historical figures have been proposed for removal because of their controversial political histories, maybe it makes sense for art to be as nonobjective as Herrera’s. There is also the formal comment to be made that the work can be seen as part of the grid formations that determine so large a part of Manhattan, where buildings and skyscrapers necessarily maintain right-angled, geometric relations. Still, we remember that sculpture began as a memorial, usually the commemoration of the dead. Thus, Herrera’s art evades its conventional function in favor of a language comfortably ensconced within the architectural idiom surrounding it. Surely there is nothing wrong in doing so, and Herrera is so very good in her art that the notion of objective, as opposed to human, report becomes a means of celebration–strangely enough, of the human spirit! (Sculpture, after all, is a human endeavor, and not a mechanized one.) Herrera’s work may not lead to an apotheosis of emotion, but it suggests, in very beautiful ways, how form can be pleasing simply on its own terms. The show at City Hall not only recognizes the ongoing achievement of a long-neglected important artist of our time, it also represents the lively history, still extant, of a way of working that, given its origins early in the previous century, is more venerable than we may be willing to acknowledge.

Carmen Herrera: Estructuras Monumentales

Jul 11, 2019 – Nov 8, 2019

New York