Ekebergparken Sculpture Park, Oslo

The natural state does not truly exist on this planet anymore. The earth has been relentlessly turned over by successive generations. Rocks have been carved, sculpted and cut again and again; in the cuts and in their veins, one can see the work of ancient and rudimentary chisels. Rows of trees line up paths that seem to wander but that in reality are submitted to the vision of those who designed them, once upon a time. From afar, the natural landscape seems virgin, immaculate in its closed ecosystem; from up close, it bears the marks of humans, industry, and of the ineffable Anthropocene. Nature has been conquered. Or at least that is what we believe.

But an image still remains within us. Perfect. Pure. Frozen in a time where time does not exist. Immortalized by the artistic fiction of the sensitive and romantic soul. In the name of this image, we nurture fantasies, rousseauist desires of a return to nature, a nature that we are reclaiming, that we carry within ourselves, us infinitely sensitive, perfectible beings, capable of recovering all the good that brings us closer to Her.

However, this image is no thicker than our skin. Underneath it lays the corpse of death, of putrefaction, of the necrotic larvae that defecates to feed the earth. The corpse becomes plant, which becomes fruit, which becomes food, and again death: sex, fluids and necrosis, the sadistic cycle of the nature that Rousseau failed to see and that Sade consecrated in his sacrilegious yet hilarious writing. Sade against Rousseau – the eternal debate, brilliantly described by Camille Paglia (but forgotten because of his irascible and at times unjustified diatribes). When romantic passion goes after the soul to elevate it, the chthonian truth of biology and nature brings it back to earth.

Since the first gregarious communities, this very human ambivalence might have presided to the great decisions of humans regarding the fates of our planet, of society and of nature itself. In fact, great parks and urban gardens were born as counterpoints to the city of the industrial revolution. In its destructive urge, typical – as Sade would put it – of the human biological condition, humankind then felt the need to acknowledge the beauty of trees, bird songs and the saturated colors of spring.

The north entrance of Ekebergparken, in Oslo, stresses this division between humans and nature, in all the complexities, arguments and counter-arguments, ambiguities and sophisms that fueled it in prose and poetry. Paul Mccarthy’s Santa offers its sexual and childish depravation – an erotic fantasy such as those of Sade, painted in red, wielding a Christmas dildo towards the sky. After all, sex is amoral and natural – but also animal and corrupting, would add Rousseau.

The path is tortuous, punctuated by steps leading to the heights of Oslo. Treetops cover the urban landscape like lace. The landscape of a metropolis designed by fjords and water, and now redesigned, sheeted and gutted by an ambitious public and private works project. The smell of tar and wet concrete lingers under the subtle fragrances of dry leaves and trampled grasses.

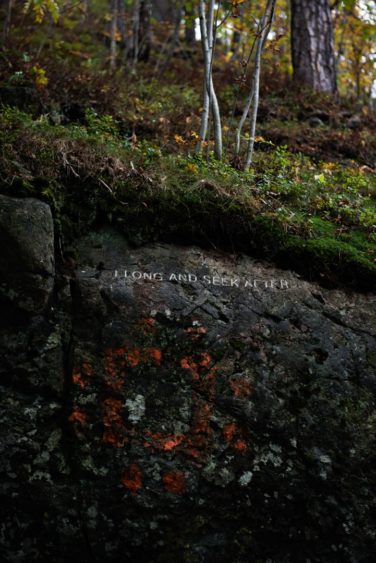

The sculptures of the park are serene witnesses of our sensorial impulses. And the rocks, accidental sculptures of nature, are the stratified marks of time. From the Ice Age to the modern era, stone has been the firm element of the Great Foundation; it informs us, with the usual and layered slowness of sediments. It is on those metamorphic and sedimentary masses, where Oslo’s first humans settled, that Jenny Holzer conceived one of the most significant, and yet discreet, works of the park: Cliff Sapho echoes the verses of Greek poetess Sapho, engraved in stone. Only the most attentive or those who abandon themselves to dissolution into space will find it. At first, one sees the clarity of the right angles of the H, then the perfect circle of the O, and then one can perceive the presence of a voice, deliberately immortalized into the stone. Holzer highlights the beauty of Classical Antiquity writing and exposes it to nature and erosion – the most natural way to forget. Between memory and oblivion, Holzer demonstrates the intelligence of the feminine voice, discreet, indeed, but beautiful and insightful. Elsewhere in the park, the same verses appear, randomly scattered, as a wandering voice that finds us and abandons us on the forest trails.

The trails part into several directions at the belvedere, where stands Jaume Plensa’s sculpture, an anamorphic face watching a unique view. To the east, the trail becomes steep after James Turrell’s Skyspace, a work that is as magnificent inside as it is outside, although they feature radically different materials and atmospheres. Inside, a chapel of light and color, with an opening to look at the often grey and rainy sky, and outside, a pond and its aquatic plants circling around the open dome of the sculpture/installation. But close by, the Chapman brothers abruptly interrupt this feeling of peace and meditation. Sturm und Dang is an allegory of war made of piled up skeletons, burnt flesh and trees. Goya, a recurring reference in Jake and Dinos Chapman’s work, is transposed from etching to sculpture, as a sort of monument to human horror.

Ann-Sofi Sidén’s Fideicommissum, comes to soothe us – literally – from the terror raised by the Chapman brothers. Fideicommissum is an auto-portrait of the artist urinating. Sidén is crouching behind a tree. A timed water jet brings the final touch. The title and the representation of the work suggest the artist’s stance on Swedish traditions and legacy: she pisses on the anachronistic constructions of the past that no longer have a place in the modern era.

On the path stands a talking lamppost that lights up to the sound of voices. Tony Oursler’s Spectral Power. Φeλ (Talking lamppost) is a multimedia essay on the interpretation of the past and on what is won and lost in this deciphering act, resonating in synchrony with two other works of the artist also installed in the park: Klang, a cave of moving images and symbols, and Cognitive & Dissonance, an impressive video projection of treetops on the production of truth during the internet era.

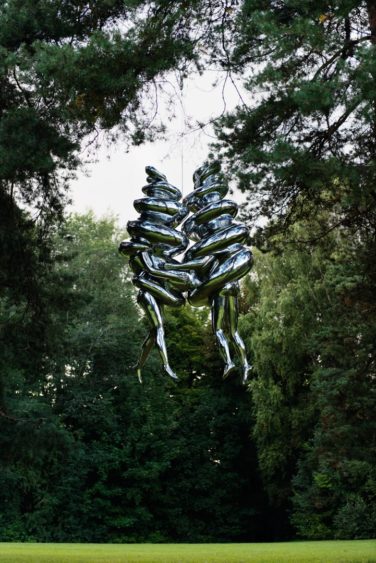

Reflections constitute the material of many of the pieces exhibited at Ekebergparken. They multiply and transform the atmosphere depending on the time of the day, the surroundings, the weather and the number of visitors. It is the case of Dan Graham’s Ekeberg Pavillion. Its glass pavilion offers a mirific play of reflections while referring to modernist architecture; Lynn Chadwick’s giant mobile Ace of Diamonds fractures the landscape by its movements and angularity and lightly reflects green hues; George Cutts’s The Dance enlivens the atmosphere with the imperceptible dance of two spirals, sinuously mirroring the sky and the surrounding grass; then Richard Hudson’s Marilyn Monroe celebrates the sensual curves of the female body, dressed in the reflection of the surrounding foliage. However, it is Louise Bourgeois’s sculpture The Couple that stands out in this group of figures, objects or proto-objects. Two amorphous bodies rise towards the treetops. The ascending movement seems to liquefy the couple, joined in undulating shapes. Underneath this sculpture, hung to a group of trees in a clearing, vibrates the lightness of complicity and love between two bodies freed from gravity, the greatest weight of existence, and floating above all concerns, and in particular above loneliness, one of the worst plagues of modernity (foreseen by famous Norwegian sculptor Gustav Vigeland in his touching Man and Woman, Adoration). It is, without a doubt, one of the most impressive features of the sculpture park.

Other works are more melancholic and meditative. Elmgreen & Dragset created a nerve-wracking moment, when a child has to make a decision. Adults are usually the ones to make decision. The child, placed at the extremity of a diving board that is calling upon a jump and leading to a point of no return, has to take a dramatic plunge into adult life. The Dilemma is a depiction of daily life and of the painful realization that every decision takes us one step away from the age of innocence, from the time when everything was allowed, and when choices, if there were any, came down to doing nothing at all or to doing whatever wasn’t useful to a society of production.

Guy Buseyne’s Reflections also constitutes a bridge between different times of life. A taciturn-looking child is meditating. Head down, he contemplates the void of the playground where the artist placed him. Again, here is a child emulating the dispositions of adults, as if searching for a meaning life does not hold. The small scale of the sculpture brings it closer to the children who come play in the garden and who keep it company everyday, in its inscrutable loneliness.

Close to Reflections are the oldest artists and pieces of this huge natural and artistic complex. There is the unavoidable Salvador Dalí, whose Vénus de Milo aux tiroirs constitutes one of the collection’s most fascinating works. Dalí echoes Freudian theories on the interpretation of dreams and shows, with his Vénus de Milo, our inclination for secrets and for repressing our most intimate fears into hideouts, drawers and closets. Auguste Rodin, meanwhile, sculpts a caryatid collapsing under the burden that was handed to it by classical antiquity. The Cariatide tombée à l’urne is a figure yielding under the weight of the past. La grande laveuse and Venus Victrix mark the return of classical style for the woman seen by Pierre-Auguste Renoir.

Further up, Damien Hirst’s female angel stares at us with candor, indifferent to the human gaze that desecrated it and dissected its biological construction. The sacred angel has become profane, because art is amoral, nature is amoral and humans tend to be amoral. And over there, in the distance, even further up, resonates The Scream of Marina Abramovic’s, shouted by any visitor: a transposition of Edvard Munch’s homonymous painting that reveals the most animal of human sounds.

It is raining steadily. Water accumulates into Roni Horn’s Air Burial (Oslo), a translucent, delicate vessel; Fujiko Nakaya’s water vapor dissipates among the trees, creating an atmosphere worthy of a Nordic crime novel. Water brings life to the most remote corners of the park.

The body becomes weary. Muscles weaken, blood pounding in the veins. Ekebergparken is a magnificent, unique place; one could count such places on the fingers of one hand. It is a museum and an anti-museum. Natural and artificial. With no beginning and no end. One wanders around, guided by senses, and often gets lost.

The desire to gather a remarkable array of works and artists in a public park suggests an uncommon collector’s effort, which is carried out by a non-profit foundation that views this project as an engagement to democratize access to art and to ecological practices. It is probably one of the most significant and interesting political projects in the cultural field, and an example to be followed, if not reproduced, by other countries, in accordance to their local and cultural specificities. Ekebergparken is also the perfect synthesis of a sophisticated nation, proud of its natural landscapes and of their profound complexity and dramatic composition, which it seeks to protect, as contradictory as this may seem. Here is, in summary, the Norway of fjords, mountains, forests and glaciers, full of life and duplicity, where the memory of nature and the memory of art are in everyway superior to human memory.

Planning your visit:

Ekebergparken Sculpture Park is freely accessible to visitors every day of the week. As most Norwegian cultural institutions, operating hours are relatively short and it is therefore recommended to carefully plan your visit. 42 sculptures are displayed around the park along its numerous trails.

James Turrell’s Skyspace is only open on Sundays from 11am to 4pm; and Fujiko Nakaya’s # 18700 Oslo – Blinder only operates at certain times: 12:30, 2:30, 5:00 and 7:00 (it does not operate on Mondays and Wednesdays).

Ekebergparken is a natural park covering several acres with a rich and well-documented natural and geological history. Trails are sometimes steep and access to some of the artworks requires perseverance, a spirit of exploration and a good dose of determination.

Wear comfortable clothes and shoes and bring a light snack and a lot of water.

The local restaurant offers a beautiful view of Oslo and a menu including Norwegian specialties, but it is pricy.

We also recommend you visit Lund’s House, which hosts the museum of the park and a gift shop where you can find information on the site. There are no available maps on site and it is therefore recommended you download and print them prior to your visit.

Address: EKEBERGPARKEN, Kongsveien 23, N-0193 Oslo