Horizon

As regards the horizon – the limit of our view which manifests itself as a line where the sea and the sky meet – we know not that it does not exist, but rather that it designates an unattributable and nonlocalizable place. Moving with us, it is imaginary par excellence, in the sense that it serves as a medium for carrying away our imagination and our reveries. However, this horizon line has a certain consistency, even a certain substance, a physical presence that artists wanted to bring into play in their sculptures. Through some of their works, we will see that the horizon, which initially appears to be more relevant to painting and representation, also has a power of appeal for sculpture. Basing oneself on the horizon and measuring oneself against the horizon are the two ways in which this “chimerical” (or fanciful) line can manifest itself concretely in sculpture.

Basing oneself on the horizon

Even though the horizon is imaginary, artists have identified the permanent stability that it provides when viewed in the landscape. It is always there, always far away, the limit that makes it possible to distinguish top from bottom and near from far. Thus, it is a fundamental reference bearing for orienting oneself in space. From the first navigators to today’s airplane pilots, all base themselves on the horizon in order to move, to advance and to position themselves in space.

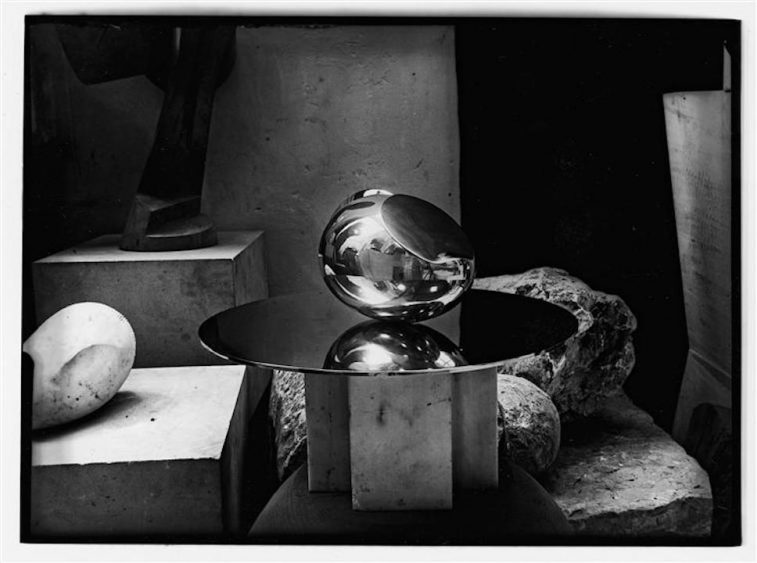

Transforming the imaginary line of the horizon into a stable edge: this is an issue of contemporary sculpture. For example, we can see this with Janine Antoni, who, in 2003, filmed herself walking on a rope in order to bounce better on the horizon, which became tangible in the landscape, or with Markus Raetz, whose bronze head placed in front of the sea in Norway (Head, 1992, Vestvogoy) changes its angle of inclination as if by magic, according to the place from which it is seen. In keeping with Brancusi (The Newborn, 1930), there is an identification in play here between the horizon and the base of the sculpture, a base that serves not to isolate the work from its general context, but to make it appear fully in its context. Thanks to the positions that the viewer must explore to see the head, there is a dialogue and a deep reflection on the place of man in nature, no matter how unfamiliar it is. When there is a horizon, there is always a relationship, a relationship between the observer and the distant, between the spectators who make simultaneous experiments in sculpture, between the spectator and the sculpture that is metamorphosed under his eyes, and between me and myself. The horizon expresses the necessary distance from me to me without which the ego would collapse, since, without it, it would not be possible to see there while being here. It is this distance that enables me to project myself on the horizon while keeping my feet anchored on the ground and to return to the point of departure of feeling in order to test the surrounding spatiality. In the case of Markus Raetz’s Head, another dimension is added: that of the memory. We see the sculpture “the right way up” although we have just seen it “upside down”, but above all, for a long time, we have seen an object of no determined form, like a solid, dark stain standing on a pedestal. We must move around it to suddenly see the head appear, but, even when this circular movement is completed, the head does not remain identical. Far from standing still on its pedestal, it rocks from top to bottom, forcing us to synthesize different experiences emanating from one same object. The fact that the sculpture looks at the landscape with the head at the bottom or at the top refers to another dimension of the horizon: its function of separation between top and bottom. However, in extreme conditions, without reference points, it is very difficult to know whether it is the sky or the sea that we see on each side of the horizon. Our feet alone prevent us from being subjected to vertigo (which, it seems, would be one of the causes of airplane accidents in the Bermuda Triangle). Inverting top and bottom in relation to the horizon, experiencing “the blue of the sky” instead of the blue of the sea, is what Markus Raetz’s sculpture invites us to explore.

Measuring oneself against the horizon

The figures that will go to the horizon must proceed in stages. The artist must mark stages, stations which allow him to measure and project his own body in the surrounding space. This is an old concern in treatises on perspective, of which the most exemplary is probably that by Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes (Elemens de perspective, 1799) where, in the last image of the book, he represents man faced with the void of the landscape, without any architectural scale. The horizon alone acts as his bearing for moving forward into the distance. The same idea is at play in a recent work by the artist Francis Alÿs: he asked Moroccan children to move forward in line in the water towards Spain while Spanish children did the same on the opposite shore on the other side of the sea, each holding a makeshift boat made from a shoe (2007). On either side of the horizon – this could be the title of this performance by Alÿs, which reactivates the horizon as a possible place of encounter beyond arbitrary human borders.

But, as we see with these examples, the sculptural horizon plays a role that is all the more crucial when photography takes it into consideration. Looking at tourists’ photographs of the Peine del Viento (1999) by Basque sculptor Eduardo Chillida, we no longer know how high we are, nor whether the various sculptural elements are extended or restricted by the horizon. However, the multiple variations on the heights of the horizon in the photographs should not make us forget that the horizon is always located at the height of the observer’s eyes. It was the Florentine architect Filippo Brunelleschi who, in the early fifteenth century, discovered this coincidence between the limit of the visual field and the height of the observer’s eyes. At least he was the first to have used it for his art. This discovery was applied in all other arts, as evidenced by the establishment of perspective in Renaissance painting. The three elements, Chillida’s “combs”, involve the landscape, of course, but also the origin of the person who contemplates the landscape, from the place that the person has to find in order to experience their own point of view, to engage in the landscape and to vary their experiences. The Peine del Viento (“Combs of the Winds”) are all ways of showing the presence of the horizon and making us sensitive to its presence. If the horizon frequently invites contemplation, it also functions as a powerful means to find the height of the point of view we want to experience.