Interview with Manon Thirriot

Manon Thirriot just spent a month at the NEKaTOENEa creation residency, at the heart of the Abbadia estate in Hendaye, in partnership with La Malterie of Lille and as part of the STARTER program that helps young college graduates acquire professional training. We talked with her about her artistic practice and her residency in the Basque country.

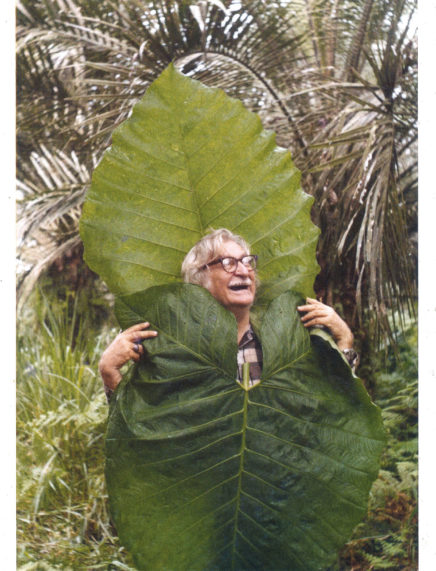

“The common thread of my work stands in part in a great fascination for nature as well as in the desire to travel and experience the landscape.” During your fourth year at the Nord Pas-de-Calais art school in Tourcoing, you decided to go abroad completely on your own. A voluntary uprooting so to speak, which, through encounters and experiences, brought you to include natural, organic elements into your artistic practice. Could you tell us about this personal journey?

I have always wanted to forge myself an image of what could be unknown territory. But it remained at the stage of a project. After graduating, I wished to get out of my daily routine and to distance myself from the educational frame, which had always surrounded me. So when I had the opportunity to spend my fourth year at ESA (Ecole Supérieure d’Art) abroad, I decided to build my thoughts on travel through my own experience, which ultimately became the research subject for my dissertation. Spontaneously, I specifically directed my research on the notions of adventure and exploration, which constitute and nourish the image of the “artist explorer” in contemporary art, by drawing a parallel between these themes and my own whereabouts.

Today, exploring by foot and the desire to experiment with the landscape and to question its plasticity have become the underlying thread of my work. This approach values first and foremost the experience and the memory of a place that I explore to project my artistic work onto it. My work is therefore intimately linked to the place in which I evolve. The result of my itineraries extends into installations, photography, or video.

This particular attraction for natural sciences through the idea of associating natural elements to my practice can certainly be explained by an awareness of environmental issues. There is a lot at stake and it is all at the heart of public, political and ecological debates of our society. It therefore seems important to me that my practice remains as close as possible to my personal convictions.

Could you tell us about two of your projects: Traces, the installation of a block of red earth made in Dawalliny and brought to the beach of Perth (Australia), and Red Earth, a site-specific installation in the Australian desert, created in collaboration with artist Matthew McAlpine? They are both strongly connected to the notions of land and memory, but also to an ephemeral temporality because for both of them, it is ultimately nature that will determine how they will evolve.

That’s right. For about nine months I travelled throughout Australia. I worked on a wheat farm in Buntine, Western Australia. The farm belongs to Stuart McAlpine, who exports most of the crops to Asia. Stuart McAlpine is considerate of climate change and he is famous in the region for using a very eco-friendly farming system, using as little water as possible. This encounter was symbolic. Living on this land for three months brought me a lot more than a mere professional experience. Through this place and these encounters, I comprehended this reality as a discovery of isolation. I learned to live with these men and women who chose to isolate themselves from the rest of the world. When I shared my wish to work with red earth, Stuart immediately put me in touch with his son, Matthew McAlpine, an Australian artist who uses earth as a primary element of his work. He creates paintings and installations using it as a natural pigment. Intrigued by his plastic approach and the desire to work in situ, our collaboration came quite naturally.

The Traces project is part of a compilation of video performances from our collaborative work. In the video appears a small cube of frozen red earth that thaws in the sun and dissolves in the sea. Through this artistic gesture, we wanted to underline the importance of what this earth symbolizes. It can be found on 84% of Western Australia and is first and foremost the emblem of aboriginal art. The presence of the aboriginal people on Australian land is currently at the center of many debates. The block was made in Dawallinu. We then installed it on a beach in Perth. The choice of the place was important. Perth is a new town that constantly grows and spreads over Western Australia. We noticed that the red earth, which used to be widespread, seemed to gradually disappear and to be replaced by new constructions.

You stayed in residency at NEKaTOENEa (Hendaye) for a month, within the STARTER project that was implemented by La Malterie in Lille and created in collaboration with the Ecole Supérieure d’Art de Dunkerque/Tourcoing. Is it too soon for you to look back at this residency? Did you discover places, artists or new landscapes?

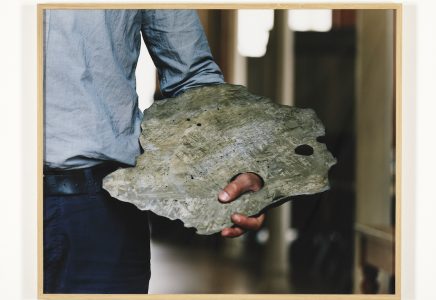

During my residency at NEKaTOENEa, I wanted to develop a reflection around collected objects. While exploring, I always take samples, I gather and collect either recent objects or remnants of some kind of archeological form, past or present. This gesture can seem common, but to me it has a true plastic relevance. It is a form of documentation of actions, a piece of evidence. The micro-asperities of these objects lend themselves to interpretation and to a sort of escape. I accumulate these objects, which then become a collection of archives of my wanderings, a protocol that I also follow with photography. Here at NEKaTOENEa, my whereabouts became more scientific.

The presence of environmentalists on the Abbadia estate allowed me to be accompanied by geologists or naturalists who could offer me a more detailed description of my itineraries on the Basque coast. I mostly explored the Pointe-Sainte-Anne, in the Erdiko-Ura bay, where I was at first struck by the work of erosion that is redefining the outline of these ever changing areas. But I was also struck by the whole ecosystem of the intertidal zone. These observations led me to question the evolution of the coastline and the environmental and ecological relationships that depend on it. Since I couldn’t collect large quantities on the estate, I had to think about how to transfer these objects by looking into different processes to come up with a series of samples through molding.

By using clay or alginic acid, for example, I create negative prints on flysch, the sequence of sedimentary rocks that constitutes the cliffs. I also directly ink the object or use cyanotype, a photographic process by emulsion that allows a detailed transfer. This print repertory will take the shape of small booklets reflecting on all the micro and macro events I was able to study on the estate and it will later be integrated to an installation. This approach leads me to work outdoors and to gradually put together a portable workshop/laboratory. Elke Roloff and Aintzane Lasarte, mission coordinators at the residency NEKaTOENEa, have greatly helped me in getting in touch with scientists and their network by directing me toward several cultural institutions such as the Centre d’art Image/Imatge in Orthez, or the Bel Ordinaire in Pau, for example.

Since I came back to Lille, I continue my research on erosion. I recently started collaborating with artist Rémi Couvreur in order to draw parallels between similar notions in different practices. Together, we research the question of transfered objects in our respective explorations. We try to extract prints of cliffs through the technique of molding.

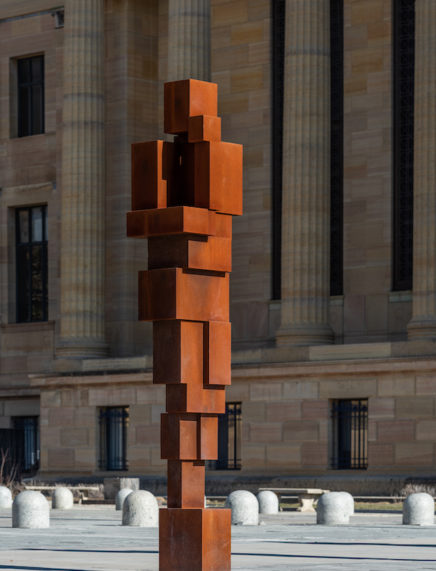

During your residency in the Basque country you had the opportunity to visit the sculpture garden of La Petite Escalère. Could you tell us what struck and compelled you the most there?

When I came to La Petite Escalère with Elke Roloff, I had the pleasure of meeting Corinne Crabos, who passionately introduced me to the garden. It happened to be a cloudy late winter day… But no matter what the conditions, I believe this garden will never fail to charm. The rain revealed the beauty of the displayed works of art under a new light. Through the history of the garden and a few epic anecdotes, Corinne quickly managed to share the values of this place, which, to me, inspires a lot of love and sharing. As any artist who comes to this garden for the first time, I think this place triggers two different states of mind: admiration and inspiration. Furthermore, I would add that I was pleasantly surprised to see how all the sculptures manage to coexist in the garden. In this verdant space, each one of them seems to have found its place, very perfectly and very naturally.

Born in 1993, Manon Thirriot lives in Lille. After obtaining her DNSEP (diplôme national supérieur d’expression plastique) in 2016 from the ESA (Ecole Supérieure d’Art du Nord-Pas de Calais Dunkerque Tourcoing), she soon entered La Malterie where she was selected for the project Starter, a program aimed at helping young college graduates in acquiring professional training.

manonthirriot.com