Martin Puryear’s Big Bling at the Madison Square Park, New York

Opening on May 16, the Madison Square Park will present its thirty-third public art exhibition that will be on view for the rest of the year. Many of those who frequent the park, like I did for several year working nearby, got into the habit of anticipating the new piece every spring. After the winter – when the park and nature in general ‘close’ themselves-, the park slowly opens up and gets alive week by week during the spring, first with the trees and planted flowers blooming then with the new artwork that is selected and mounted for that year. In 2016, this is a colossal sculpture by renowned American sculptor Martin Puryear whose work has been most recently shown in the city in an exhibition entitled Multiple Dimensions at The Morgan Library and Museum this past fall, where mainly works on paper and some maquettes for public sculptures were on display. One of the maquettes shown there already announced the formal language of Big Bling.

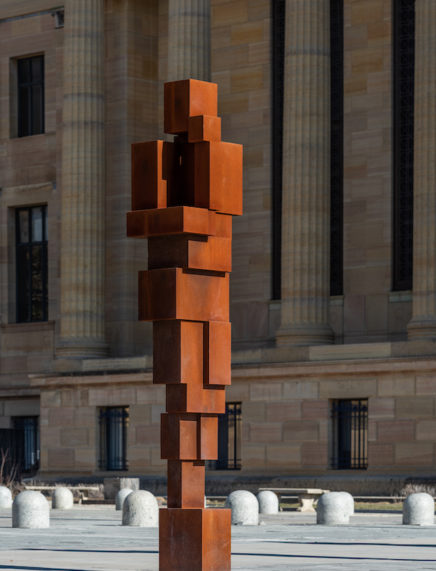

The large-scale sculpture’s somewhat abstract, somewhat biomorphic shape is a signature element of the artist’s vocabulary however its scale exceeds anything he ever created before, including the numerous public art pieces he was commission to create in Europe, Asia and the United States. With its height of forty feet, the piece will be in direct dialogue with the surrounding architecture of the city that contains such historical high-rises as the Flatiron Building or the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company Tower, both built in the turn of the 20th century. The core of Puryear’s sculpture is a wooden structure – another signature of his – covered by chain-link fence all around and topped with a gold-leafed shackle. With its architecture, materials, and shape the piece conveys opposite meanings without giving in too much to one-side or the other and at the same time without giving itself away too easily. While the transparent wooden structure invites the viewers penetrating sight and brings the sense of lightness and almost of a movement to it, the metal fence denies any entry and makes the piece more static, anchored and somewhat sealed. Between its open structure and relatively closed form – apart from the amoeboid opening in its center – the piece leaves the viewer in a place where the notions of limitation and freedom play interchangeable roles. We are invited but at the same time excluded, kept outside. In Puryear’s artistic vocabulary, this metaphoric game between inclusion and exclusion is drawn from rich historical and personal references and which are always allusive to the viewer. Defying a purely intellectual approach or interpretation, Big Bling guides us towards a more meditative or introspective mode of perception. This visceral language is very much of the artists own. His sculptures often invite a more primal approach to interpretation that doesn’t happen in the grounds of words and concrete meanings but rather in the terrain of our instincts, free associations and experiences.

The peak element of the sculpture, the shimmering gold shackle, only adds to the game of opposing meanings and impressions. While at first sight the piece can be seen as an innocent-looking stylized animal-like creature that sits in the park like an Eastern bunny waiting to surprise the bouncing kids around, the chain-link fence that covers the entire surface of the sculpture and the well recognizable shape of a shackle evoke heavier and darker associations. Barriers and locks come to mind where freedom of movement and maybe even self-expression are limited or rejected. Or is it trying to conceal something from us like a Trojan horse that shows up in the middle of the city overnight? Not only that we the viewers are denied access and therefore may feel excluded, but the piece – or the creature – itself seems to be locked down. Meanwhile, the sculpture’s title offers a more playful cultural reference that can take one back to the safer grounds of everyday urban life and its cultural references. The term “bling” is rooted in the 1990s urban youth and rap culture, referring to flashy jewelry and accessories that were named for the sound generated when worn. In the urban slang it is also used as a synonym for over the top, hideous and wholly unnecessary.

Such divergent notions combined with the sculpture’s scale offer a powerful experience that park goers may lament on for the rest of the year while strolling between the trees, dog runs and squirrels that endlessly chase each other across the fields and which are as much inalienable parts of the park as the public sculptures became in the past twelve years. Whether one sits on one of the park’s benches and immerses him/herself in such thoughts while having lunch, walks by the park on the daily basis or just happens to be there for other reasons, the sculpture may give the feeling that while provoking the viewer to tap into his/her own intuition to access it, its ultimate meaning may as well remain locked away.

Martin Puryear, Big Bling

Madison Square Park

May 16, 2016 – January 8, 2017