Movement as the Essence of Life. Jean Tinguely in the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam

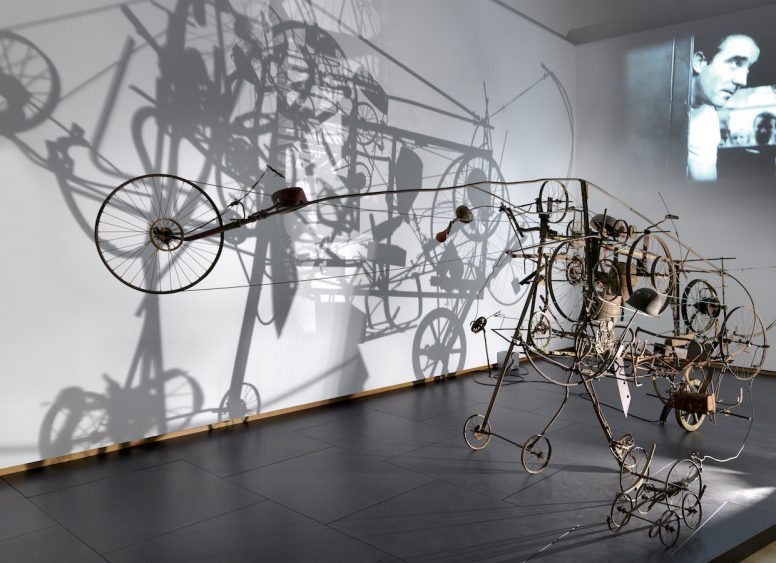

Say Jean Tinguely and people start smiling. Everybody knows his humourous moving machines of old bicycle wheels, rusted iron and scrap metal. Their sheer uselessness mocks the utility-thinking of the machine age. Which is the framework of The Machine Spectacle, an exhibition the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. Over a hundred machine sculptures, films and drawings shed light on Tinguely’s artistic development and ideas, from his love of absurd play, his mockery of the art world to his fascination for destruction and ephemerality.

If you can, take the chance to visit. It’s a great opportunity to see, hear and physically experience the moving sculptures. It’s quite challenging for the Stedelijk Museum to operate them, given the fragile nature of their construction. That they don’t work continuously only raises our expectancy. People are patiently waiting until Tinguely’s Méta-Machines come to life, with their twirling or swaggering movements and creaking sounds. Each with its own character and expression. Tinguely addresses all our senses, and film fragments add to the dynamic atmosphere. The only thing lacking in this indoor exhibition are the profusing life-giving water jets of the Fountain Sculptures.

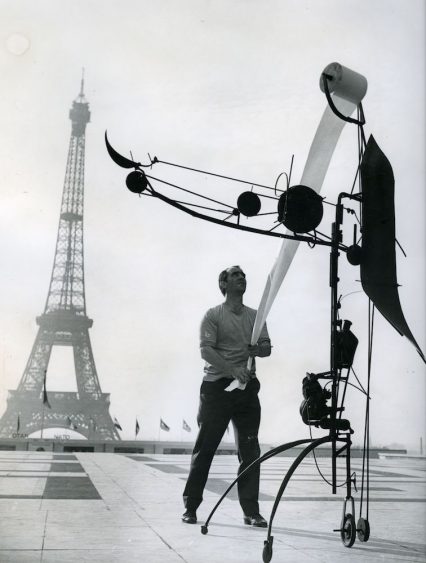

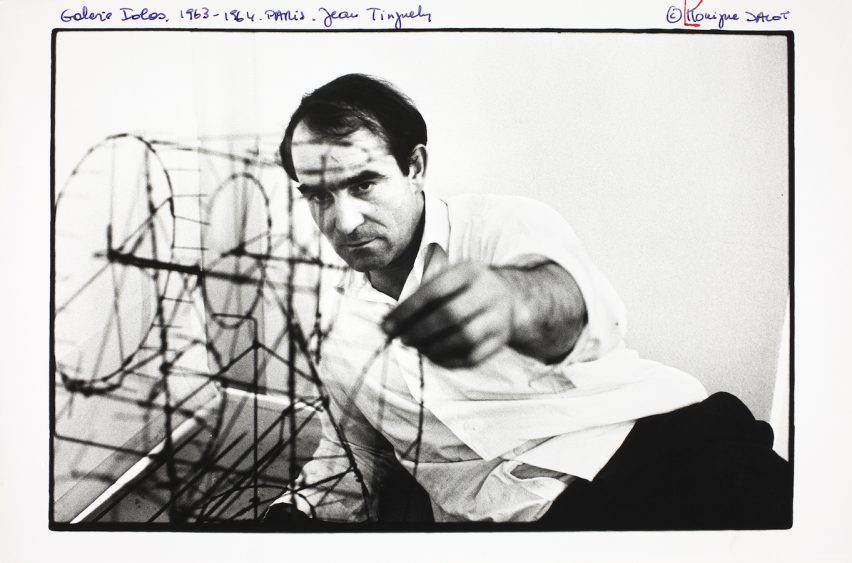

In 1944, the Swiss artist Jean Tinguely (1925 – 1991) started his career in a Bazel department store as a freelance window dresser. People stood agape with wonder about his displays with rotating cogwheels of metal thread, influenced by Bazeler artists Walter Bodmer and Robbert Müller. Tinguely had a keen eye for new developments and publicity. At the Basel School of Design, he avidly absorbed the ideas of the early avant-garde. He was interested in Dada, Constructivism and Suprematism, when artists started to experiment with sculpture in motion. Tinguely was part of the kinetic art movement. With Alexander Calder and Pol Bury, he was one of the artists in the 1955 groundbreaking exhibition Le Mouvement at Galerie Denise René in Paris. In 1961, he was co-curator and participant in the famous exhibition Bewogen Beweging (Moved Movement), which featured 222 kinetic artworks at the Stedelijk Museum.

In 1952, Tinguely moved to Paris, in the footsteps of his friend, the artist and dancer Daniel Spoerri. And in Paris he was to meet his second wife, the French artist Niki de Saint Phalle (1930-2002). They proved to be a productive couple, teaming up for his and her projects.

Being frustrated by the static nature of art, Jean Tinguely chose to make moving sculptures. In his first works, dating from 1953-1959, Tinguely is inspired by Kasimir Malevich and Jean Arp. Powered by hidden engines, he literally sets abstract compositions in motion. But soon he abandons abstract art and falls in love with the machine.

With his do-it-yourself drawing machines (Méta-Matics), and his self-destroying machines, Tinguely takes a critical stance toward art making, just like Marcel Duchamp did with his « readymades ». Duchamp is credited to be the first to introduce movement in sculpture. In 1913, he mounted a bicycle wheel on a stool and signed it. It was his first readymade. Duchamp wanted to question the cult of the individual artist and the deification of art objects in museums. And so did Tinguely. In 1959, he invited everyone to Galerie Iris Clert, to create an artwork with his Méta-Matic do-it-yourself drawing machine. You only had to press a button. Thus art was democratized, and it was mechanized. In the Machine Age, Mechanical Art was the headline of an American newspaper in 1960.

Like many of his collegues in the sixties, Tinguely revolted against the sterile, static atmosphere of the museum. When invited to exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art, he challenged the oldest and exemplary art institution by creating a huge white machine which exploded with huge uproar in the pond of the sculpture garden. Homage to New York (1960) was Tinguely’s first self-destructive machine, « an ephemeral, temporary work, like a shooting star, emphatically not meant to be collected by museums. She just passed, so that people could dream about it, talk about it. And that’s it, the next day there was nothing. It was a machine who committed suicide » the artist stated.1

His 1962 exhibition Dylaby, at the Stedelijk Museum, was equally transient in nature. With his artist friends, Tinguely created an interactive DYnamic LABYrinth, which existed only three weeks. Fortunately, it is filmed by the Dutch filmmaker Louis van Gasteren. It is exhilarating to observe the public, stumbling in the dark, tentatively searching for their way out through narrow passageways with false doors. With his interactive-event-sculpture Tinguely was ahead of his time. « It looks more like a fair or a circus! », a critic frowned. But the entertainment industry was enthusiast. Walt Disney Studios invited him to collaborate, which he didn’t. And the American broadcasting company NBC asked him to present a performance on tv. Which he did.

When asked where the film had to be shot, Tinguely chooses the Nevada desert. This location, where the first nuclear tests were carried out, makes his third self-destructive machine serious matter. The film shows Niki de Saint Phalle and Tinguely hunting for redundant objects of consumer society, such as an airco, a refrigerator, a toilet or watertank, cumulating into a large machine sculpture. When in 1962, at the height of the Cold War, this artwork explodes, it embodies the fear of the total destruction of humanity by its own technology. Hence the title, Study for an End of the World No. 2.

Aged 60, the flamboyant Tinguely had to have heart surgery. His work became more gloomy. In 1986, he witnessed a devastating fire turning a neighboring farm into ashes. Afterwards, Tinguely reclaimed scorched wood, animal skulls and remnants of agricultural machinery, made by the Mengele company. His Mengele-Totentanz (1986) is the impressive closing chapter of the Stedelijk Museum exhibition. In the scarcely-lit space, with juddering movements and piercing sounds the objects come to life, to perform a danse macabre. In this altar piece, the artist who regarded movement as an embodiment of the transience of life faces death.

« Only in movement, we find the true essence of things. We are afraid for movement, because it stands for decomposition and our own disintegration. I believe in change. Do not hold anything fast. It is beautiful to be transitory. Live in time, with time. It flows through your fingers. Time is movement and cannot be checked » Tinguely declares in his 1959 manifesto For Static.

Jean Tinguely – Machine Spectacle

Stedelijk Museum,

Amsterdam, the Netherlands

October 1, 2016 – March 5, 2017

stedelijk.nl

1 Source