Nancy Holt’s Sun Tunnels:

interview with Dia curator Kelly Kivland

From 1973-1976, the American artist Nancy Holt (b. 1938 d. 2014) produced a large-scale land art installation in Utah’s Great Basin Desert entitled Sun Tunnels. In 2018, the Dia Art Foundation acquired Sun Tunnels with support from the Holt-Smithson Foundation. Raisa Rexer spoke with curator Kelly Kivland in December 2018 about the acquisition, its place in the Dia collections, and the foundation’s approach to the stewardship of its land art sites.

How did the idea for this come about? Tell me about the process of deciding to acquire it.

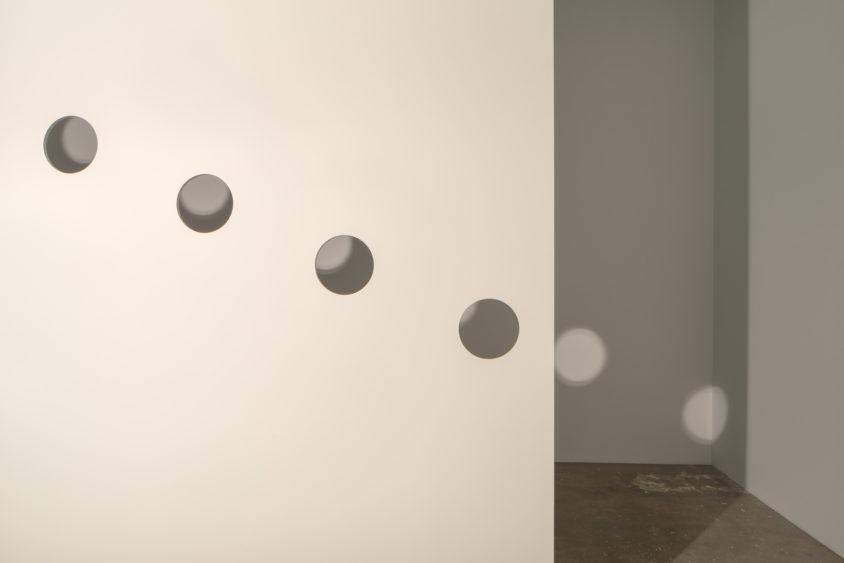

Our relationship with Nancy began in 1999, when she gifted Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty to Dia. That helped cement an ongoing relationship with Nancy thereafter. When her exhibition “Sightlines” opened at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts, a group of us went out to celebrate that occasion. I had a chance to meet her then, and to visit Sun Tunnels with her, and we remained in communication with each other. I was fairly new to Dia at the time, but there was already some interest in other land art works that Dia might be able to become the owner of, given that we are so poised as stewards of other sites. When she passed away in 2014 we then began thinking quite seriously about the idea of acquiring the work, and decided it was a priority. It took a few years, mainly because of the pace of moving things from her estate to the Holt-Smithson Foundation. That was finalized in summer of 2017 and then thereafter we sped into high gear to acquire the work from the Holt-Smithson Foundation. We acquired Sun Tunnels as well as the room installation currently on view in Chelsea [through March 2019] called Holes of Light. Holes of Light was realized around the time that Holt was starting to think about Sun Tunnels, so they have real resonance with each other; one is an interior installation utilizing light and shadow and directionality, and the other an exterior iteration.

What is it about Nancy’s work that speaks to you, personally and in your role as a curator? What makes her work timely?

My interest in Nancy’s work really started for me with meeting her and realizing the breadth of her work through “Sightlines.” I had known a bit about her from some of her video work but had never had really a chance to see her work—I don’t think many people did—until “Sightlines.” In the 1960s, Nancy worked in audio, video, photography and concrete poetry. All of this work was exploring space and location, the idea of interior and exterior and her own place in and movement through these sites and how she remembers them and documents them, and that for me was quite interesting. Then, in 1971, she moved to sculpture with her “Locator” works, sculptures made from plumbing pipes. And shortly thereafter she began making room installations and then right after that she started work on Sun Tunnels.

Like other artists of her generation, she was preoccupied with landscape and sight and the nuances of observation, but her approach was very different. Many people, of course, have written about the viewer and the agency of the viewer in minimalist work and post minimalist work, but for Nancy it was imperative to the experience of her art. Her work is very rigorous—she was a biology major at Tufts, and she’s thinking with that background—but then there’s a sense of play and agency and freedom that she allows with these works. With the “Locators,” for example, you look through them but each and every person will see something slightly differently. In the room installations, the same is true. People will walk around them and really have their own experiences, and their own time with them, their own duration within them.

She’s so timely right now not only because she’s was a woman working prolifically in the later twentieth century but because of the combination of the scale of her work and the subtleties of her approach. Her room size installations in 1973 and 1974 are huge. They take over an entire room, create a room within a room. It’s such a bold move for an artist in the early 1970s, a woman artist, to decide at that time on the occasion of her gallery show in New York to create a large room that essentially is playing with emptiness, with light and mirrors and reflection and shadow, instead of filling it with objects. For the current generation of artists who are working this way, who are really thinking about how both interior and exterior sites influence the artist or how the artist responds to a site in making work, she is of real value, because she strips this conceptual basis of its object thinking and instead thinks about how to create an experience. She does so in the simplest terms, but with great rigor.

To what extent do you think her unique approach is conditioned by her gender and the context of working in a very male-dominated field at the time?

There are so many female artists [of the period] who were somewhat under-recognized, and were making work that may well have been a response to the dominance of male artists.

To be frank, I do see this as a counter to the Mesolithic structures being built by men. That’s not to say that Sun Tunnels is not that; she creates huge structures in the desert and orchestrates the whole endeavor with a whole team of men—engineers, astronomers, construction workers. But although her structures are large, they envelop a body, they are very much about paying attention to the natural rhythms of the day and the light that passes through them and the landscape that they frame. There’s an element of the mythical in the way in which she looks above and thinks about the greater powers, both in terms of how they guide our experience of time and how they influence our perception of our environment. The light, the passing of time, the motion of the sun and the moon and the position of the stars—she’s always thinking about tying our personal experience on earth to these greater processes above. The Sun Tunnels are more or less life-size “Locators,” but experienced with your body instead of your eye. They take the viewer’s perspective from the interior of the tunnel outward. In many ways, she’s asking you to look beyond the object.

How does Dia understand its stewardship for this piece, practically and philosophically?

As stewards and owners Dia’s primary responsibility is securing access to the site and understanding how we can be involved in the sustainability of the work and the greater environment. That doesn’t just mean the physical site and object, it’s also about local community efforts and partnerships. We work with the State of Utah, the road commissioner, the department of natural resources. We’re in contact with a lot of people regularly to protect these works. We also have local community partners in Utah who help with the promotion of cultural and artistic legacy of the work –The Utah Museum of Fine Arts, and CLUI (Center for Land Use Interpretation), which has a complex about an hour from the Sun Tunnels in Wendover. But our primary approach is to avoid over-mediating. The only site with fulltime caretakers is the Lightening Fields. Sun Tunnels doesn’t have any form of monitoring. We put a lot of the onus on the visitor. A lot of our work as stewards is to promote the idea of protecting these works long term. We make sure that we ensure access to the site and we are mindful of the greater environment and ways that we can protect it.

What kind of environmental role have you taken on as caretakers?

As stewards and owners of Sun Tunnels, we down the land it sits on. We’ve been owners less than a year. During that time, we’ve already begun thinking through conservation efforts of the actual tunnels themselves, and we also have to take into consideration the work’s sightlines. We are hoping to put forth in the coming years a broader plan of sustainability, not only with regards to the site but the environment around it, and how we can be involved in preserving it.

Part of what we already do as stewards is to document our works a minimum of twice a year in overhead photography, and we can see the change in the environment just tracing that history over the years. At Spiral Jetty, which we have owned for twenty years, you can see dry spells, and times when it had more water around it. Right now, it has been dry for the last four or five years, due to the super drought in the American West; you can see the effect of the super drought on the finite site of Spiral Jetty in our photographs. The scientists we work with use Spiral Jetty as a source of investigation, a micro site, a static space where you can watch this change happen. And in fact, that was very much what Smithson was thinking of, the idea of tracking and being an agent of change alongside environmental change, although I don’t know if he imagined it would be as accelerated as it has been over the last ten to twenty years.

What can this kind of land art installation contribute to debates about environmental stewardship and climate change that we can’t get in other contexts?

We don’t want to instrumentalize climate change for the benefit of a conversation around artworks that we own. But having been the owner of many of these art sites and these land artworks, we understand that we need to be mindful of the changing environment. Spiral Jetty and Sun Tunnels bring people out to incredible spaces. They spread awareness that, as visitors to this artwork you are part of that environment and looking at art in the landscape. Visitors want to protect that landscape. We are thinking through the most responsible way to contribute to conversations about environmental issues based on our role as stewards of these sites for four or five decades.

One of the events we are organizing around Sun Tunnels is a symposium in February. In addition to three art historians, we’ve invited an astronomer speaking about Mesolithic structures that track celestial change, an architect who works in environmental design and a geologist specializing in the Bonneville region who will speak about geologic change and why the site’s history is so important to the experience of Sun Tunnels. We are hoping it provides a greater context for Sun Tunnels as a land artwork, thinking about how Holt approached the land and how we can view this environment alongside this fantastic artwork. It’s part of how we approach the conversation about sustainability and land protection in terms of all of our land art sites. We want to shed light on all the ways of thinking about how a structure acts on and responds to a site—the geologic, the astronomic, the architectural—alongside the science of climate change. It’s maybe more of a subtle approach, but I think it’s actually incredibly important—not just to say, “She thought about this environment, she chose the site for these attributes,” but to really understand what those attributes are and how important they are not only to this artwork but to the history of the region, and in turn the importance of that region and that history, both for Americans and the rest of the world.