Brazilian Modern: The Living Art of Roberto Burle Marx at the New York Botanical Garden

An iconic figure, not only for art composed of living flora resulting in garden landscapes of extraordinary beauty, but also for environmental awareness, Roberto Burle Marx (1909-1994) was a leader in creating estates that took nature as a starting point but also reflected the artistic training of the artist. Born in Sao Paolo and raised in Rio de Janeiro, Burle Marx made his way to Berlin in 1928 to study painting. Two years later he returned to Rio to take courses at the National Academy of the Arts, quickly beginning to study the esthetic display of plants, although he thought of himself as a painter (there is also a show of his very good, abstractly oriented fine art–paintings, drawings, textiles–at an indoors gallery at the New York Botanical Garden [NYPG]). His first project, a garden planned in the early 1930s in conjunction with architect Lucio Costa, demonstrated what brought attention to Burle Marx from the start: the extraordinary visual weaving of plants and trees in ways that promoted not only the estheticization of nature, but also, clearly, an awareness of the fragility of plants in light of the increasingly antagonistic developments of man.

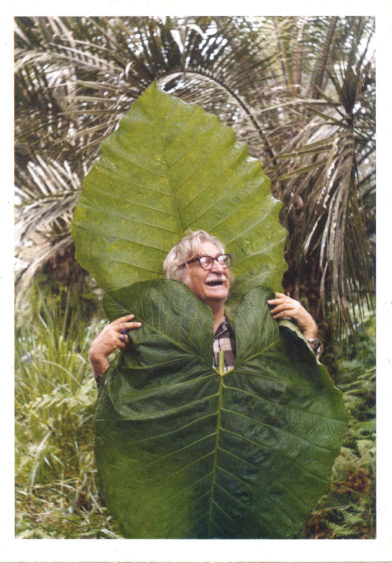

Burle Marx was not only an artist but also a horticulturalist who took trips regularly to Brazil’s rainforest, as well as an activist who very early on warned us about the damaging effects of deforestation. The NYPG’s homage to his life and work was not only a belated recognition of an iconoclast who found his creativity in sources not conventionally thought of as wellsprings of artistic inspiration, it is also a collage of startling beauty. Beginning just outside the glass conservatory near one of the Garden’s entrances, and continuing into the light-filled, plant-dense, and thickly humid rooms of the building, the plant arrangements compose a magnificent memorial to the artist, who, it is now clear, was way ahead of his time. Above all, the small botanical park is notable for its plantings of seedlings, shrubs, and trees that come not only from South America but from all over the world. Additionally, there is a gray-and-white stone walking path that is short but leads visitors through the intense attractions of the plants. There is also a tannish gray stone wall with a linearly geometric, abstract design; water flows from openings on the wall’s lower right into the pond it rises from. Seen on a weekday, when visitors come to the Garden in lower numbers, one had the time to appreciate the compact amalgam of small plants and shrubbery: philodendrons, mast trees, elephant ears, palm trees.

The exhibition, inspired by Burle Marx’s designs, makes up for its relatively small size with an intense economy of means. Plants and trees support and contrast with each other, on the basis of size, color, texture, and the kind of flora set in close contact with each other. Unlike Burle Marx’s distinguished fine art efforts, this garden, like all that he designed, is not so much a jungle as it is a place of cultivated repose. For all of the artist’s eloquence about deforestation, this homage comes across as a highly cultured environment–in which the plants, regularly set together but usually originating at great distances from each other, are experienced as part of a palette or larger picture or painting. Burle Marx was so gifted a practitioner of this kind of image-making–the term can be used despite, or because of, the fact that our transit through the path fronted by mostly exotic plants (at least for Americans) possesses as much cultural currency as it does natural attraction. The idea can only be intuited, inasmuch the walkway is more or less devoted to flora, with the important exceptions of the concrete footpath and the wall fountain with its linear, modernist incisions. Burle Marx spent his adult life collecting and displaying plants and trees, but his education as a young man was in art, so the thrust of his remarkable intuition had a double purpose: the creation of an art based thoroughly on nature and the presentation of nature in service to art.

What does this mean in light of the artist’s legacy to a world increasingly, if also hopelessly, attuned to his prophetic voice, both as esthetic visionary and moral anticipant of a rapidly diminishing landscape? While he is no longer with us, Burle Marx was not ahead of his time so much because he has been gone the length of a generation, but because what he believed would happen to our world has now taken place. It is more than terrible to consider the swiftness of the rapacity with which we are treating nature, the rainforest for example, which is not only a source of necessary oxygen and a repository for creatures adding to world diversity, but is also the source of the imagination. The mind regularly uses nature as an origin of metaphor, without which the creative impulse would be bereft. It may be already too late to salvage nature from depredations resulting from a bloated human population, not to mention sheer indifference. The point is to build places where thought can survive in light of what it imagines–no matter whether it is cultural or natural. In the amazing art of Burle Marx, it is both. This speaks to our present and our future–cultural life increasingly must address the physical outdoors as well as the interior of the mind.

One wonders if current concerns about the environment can result in imaginative forays of excellence, on both a creative and a critical or scholarly level. There is now a recently established tradition of ecocriticism in literature, and in art, some of our best practitioners, like the American Theresita Fernandez, work on installations that often take their calling from natural effects. But Burle Marx was more than an artist, as this remarkable homage at the NYBG demonstrates. Low-lying plants of muted colors vie with taller trees coming from all over the world; brightly colored flora assert a palette far more vivid than we normally come across in painting. In that sense, nature has got culture beat. Burle Marx, in his scientific exploration of the rainforest, found a way to bring back its offerings to the cities he worked and lived in, so that the concomitant experience of originality and the given attributes of the exterior world are merged in the astute placement of plants.

Accustomed as we now are to original methods of art, Burle Marx’s decision to paint with plants and trees does not seem so terribly offbeat. Indeed, we note that the subtlety and range of colors nature provides far exceeds the spectrum of oil, acrylic, watercolor. The artist was able to provide a spectacular density and range of hue, not to mention the equally beautiful structures provided by leaves, tree trunks, grasses. It was the purpose of Burle Marx to look closely at how different forms in nature might intersect and combine to create patterns and textures unable to be created by the human hand. Burle Marx was a true creative inventor, an artist devoted to the transcendent, but he did not live a life of disembodied abstraction. Instead, he felt that the natural means at hand, in the countryside not far from where he lived, could be used to build a variety of effects that not only enchanted his audience, but also reminded viewers that the elements of his garden were becoming increasingly fragile. This was already happening extensivel while he was alive, in a world in which subtleties of growth were quite literally being cut down by man. While he couldn’t do much to push back the overwhelming destruction that was, and is, an inevitable concomitant to human development and encroachment on the landscape, neither did he forego warning us about the damage coming to haunt us in the future.

Is there anything that can be done to move us away from a path marching inevitably toward oblivion? But, sadly, good or even great art cannot transform the forces that are inexorably cutting down the rainforest’s dense interior. Perhaps this was always so–artists are not famous for having enough power to change society, although their work inspires their audiences to do so. Burle Marx took the art of landscape architecture as far as anyone has been able to do so. And the garden at the NYBG is evidence of his inspiration, his willingness to allow the nature he was using for art to remain nature, rather than forcibly inducing cultural values onto values found in the exterior world. For this writer, then, the homage at the NYBG induced a melancholic cast of mind, not least because so much greater harm has been done in the quarter century since his death. Art can do a lot, but it can also only do so much–especially in the face of social forces that easily eclipse it. Even so, “Brazilian Modern” is not a memory of a place, but an active site, in which the elements of natural profusion are merged in memorable fashion. Perhaps that is all we can do, in our age of crowded humanity. Burle Marx’s estate gardens may not be all that we want, but they are real and genuine, if partial, answers to the ageless complexities of people and the environment. We need his vision now more than ever, before we are overcome by disinterest and greed.

Brazilian Modern: The Living Art of Roberto Burle Marx

New York Botanical Garden

New York

Through September 29, 2019