SFMOMA Reopens With Several Gardens, Terraces, and Galleries for Sculpture

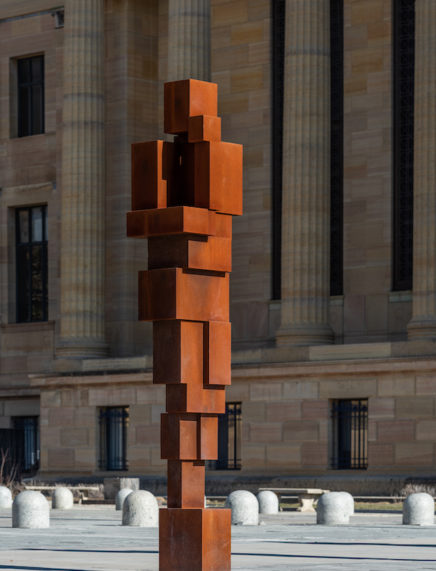

The first piece of work installed in anticipation of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art’s $610 million expansion was Richard Serra’s monumental sculpture Sequence (2006). The 214 ton intertwined figure eights now greet visitors in one of the museum’s two entrances. Lying outside of the ticketed area it is admirably accessible to the non-paying public.

The weathering steel sculpture is hard and industrial, and the rust recalls urban decay. But walking through the enormous maze is an experience almost like being in nature. The walls mimic those of a tight cavern and the iron oxide resembles the sandstone of the famous Antelope Canyon in the Navajo Nation. When traversing the colossal sculpture’s path, everything disappears but the steel and the small path ahead. It is brief, but it is like a meditative hike.

Visitors entering the museum’s other entrance are met by a twenty-six foot wide Alexander Calder sculpture, Untitled (1963), dangling overhead. Like Serra, Calder’s work now has a commanding presence at the museum. The most impressive of the museum’s many gardens and terraces is on the third floor, closed off by a “living wall” 150 feet long and 35 foot tall, embedded with over 15,000 individual plants. This wall, along with the San Francisco skyline, provides a beautiful backdrop and juxtaposition for several mostly black and bronze sculptures by Calder, Mark di Suvero, Barnett Newman, and George Segal. The Calders, however, seem to have spilled out from an adjacent gallery space that is dedicated exclusively and perpetually to the artist’s work. Currently on display are several mobiles from the 1940s and 1950s painted with the sculptor’s trademark minimalist color palette. These works are more playful than two of the dark and brutal pieces outside. The light-filled room casts shadows across the walls, which suits the lively mobiles.

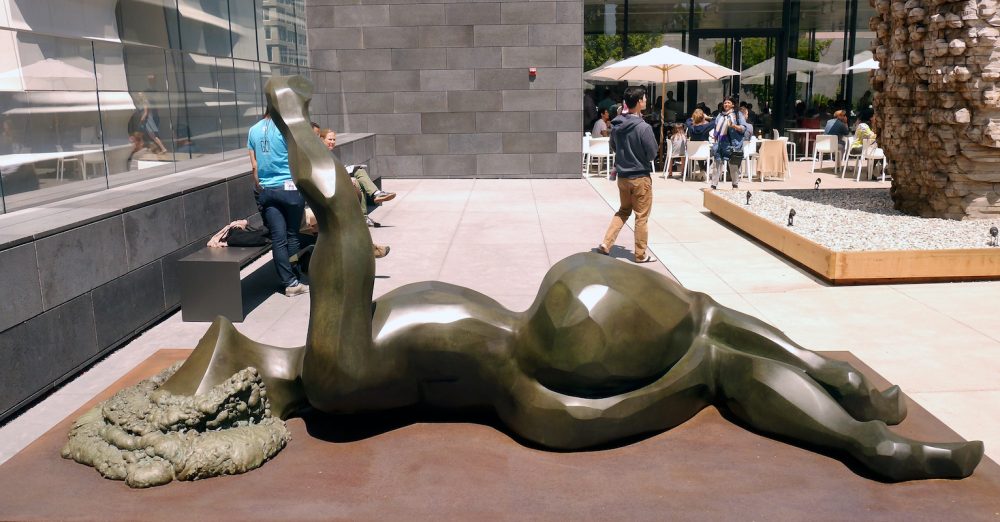

The fifth floor sculpture garden is much larger, with works to fill it, but it is also less serene, accompanied by a cafe and food kiosks. On a busy day it is not a place for quiet contemplation, but the surrounding high-rises pair nicely with the two soaring sculptures. Ursula von Rydingsvard’s sixteen foot tall cedar Czara z Bąbelkami (2006) is based on the popcorn stitches of a sweater she had as a child in a German refugee camp. The earthy and organic tower almost clashes with the surrounding urban environment, but this contrast draws attention to the form and materiality of the sculpture. Conversely, Ellsworth Kelly’s weathering steel monolith, Stele I (1973), imitates the nearby office towers under construction.

Since reopening, SFMOMA has received considerable criticism for its lack of work by women and artists of color. This shortcoming is most visible with the museum’s sculpture collection, which is defined by a number of monuments by high-profile white male artists. In addition to Rydingsvard’s contribution to the sculpture garden, however, there are notable exceptions.

Brad Kahlhamer’s Super Catcher (2014) is breathtaking. The enormous wire and bell dream catcher is intricate, sensitive, and if not fragile, adept and feigning so. Referencing the artist’s indigenous and Brooklynite identity, the sculpture combines patterns that evoke something more traditional with material and forms out of a retro science fiction film. As with so many corners of the new building, light befriends the sculpture, shimmering on the metal bells and catching the eyes of passersby.

An exhibition of new work by Leonor Antunes is also currently on display. Like Serra’s Sequence, the pieces in New Work: Leonor Antunes beg for navigation by viewers. Hemp rope, nylon yarn, and partitions hang from the ceiling in a single room lit by sculptural lamps. The installation resides in a rare corridor not filled with natural light, and the room’s dimness teases viewers, suggesting that this space might not even be open to the public. One must find out for him or herself.

SFMOMA is now the largest modern art museum in the United States. There is no paucity of space, and it is almost all wonderful. And while big names will always loom large, as they attract paying customers, grants, and press, it would be delightful to see the museum take greater risks when determining which artists’ works occupy which spaces.

151 Third Street

San Francisco, CA 94103

United States

Galleries are open daily 10 a.m.–5 p.m. and Thursdays until 9 p.m.

Public spaces are open daily at 9 a.m.

SFMOMA is closed on Thanksgiving and Christmas Day.

Last admission is a half hour before closing.