The Crowdfunding Trend

The Chinati Foundation, based in Marfa in the Texas desert, has announced last week that it had successfully raised $100,000 for the completion of a permanent installation by American artist Robert Irwin, which is expected to open to the public this summer. The fundraising campaign, performed via the crowdfunding platform Kickstarter, was launched a month ago in the hopes of raising at least $75,000 (approximately 66,000 Euros) before April 1st, 2016. If the goal had not been met, the donations would have been returned.

Raising Awareness

The creation or the restoration of large scale outdoor artistic projects seem particularly well suited for crowdfunding and fundraising in general: being outdoors, accessible to the public, either in urban or rural settings, and often created for a specific location, these works of art are primarily meant to be part of a landscape, a community, a territory. Whether permanent or destined to disappear, they are linked to the history of a place, to its population, and closely relate to the ones who belong to it. Crowdfunding therefore allows to raise public awareness on the importance of cultural heritage and offers everyone an opportunity to play an active part in the creation, the implementation and the preservation of historic or contemporary works of art which belong to this heritage. Last summer, the International Center of Art and Landscape at Vassivière Island (CIAP), located in the heart of the Millevaches Plateau and the Limousin region, launched a fundraiser for the restoration of some of the most significant works of the island’s sculpture park, which includes sixty-four installations throughout forests, prairies and along the lakeshores, and illustrate the major movements of contemporary sculpture. The “Bois de sculptures” project was launched in 1983 under the initiative of a local group of artists and art amateurs: they invited a dozen national and international artists to work with the local stone, granite, thus launching the idea of a contemporary sculpture park and creating the first granite sculpture symposium in the Limousin region. This event ultimately led to the first steps, in 1987, towards the creation of the art institution that exists today. After the completion of the center in 1991 by architects Aldo Rossi and Xavier Fabre, and throughout the 1990s, a dozen artists (including David Nash, Bernard Calet, Roland Cognet, Per Barclay and later Erik Samakh) were invited to create works specifically connected to the environment and the history of the land. Often made of natural materials, these works have deteriorated over the years and the center therefore assessed which restorations had to be prioritized. Five works were selected: Charred Wood and Green Moss by David Nash, Sans titre by Bernard Calet, Moulage by Roland Cognet, Vannhus by Per Barclay and Graines de Lumière by Erik Samakh. These restorations, which will be undertaken in collaboration with the artists, require significant financial means which the center cannot bear on its own. In order to develop a fundraising campaign, it therefore partnered with the Friends of the Vassivière Art Center and the Fondation du Patrimoine en Limousin which, for the past few years, have been increasingly involved in supporting contemporary art creation in an effort to promote the local cultural know-how and heritage. So far, the campaign has collected 14,410 Euros from private contributors and patrons. Furthermore, the Foundation has committed to match the total donations, thus raising the amount to 28,810 Euros. “Our goal is to raise the local population’s awareness of this heritage which, in fact, is theirs. Since the park is freely accessible, it is also one of the island’s first attractions visitors come to. It greatly contributes to the touristic appeal of the island, regionally and even internationally”, explains Guillaume Baudin, public art, exhibition and publication coordinator at the CIAP.

« One stone at a time »

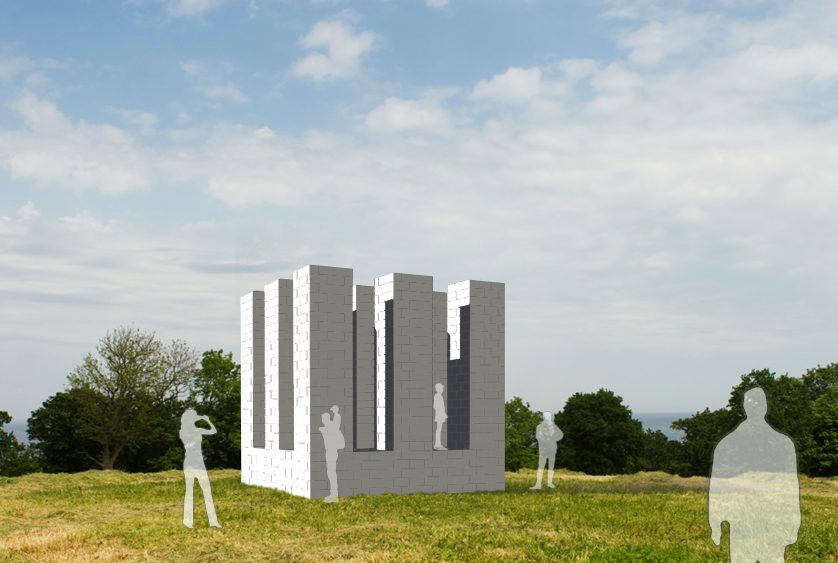

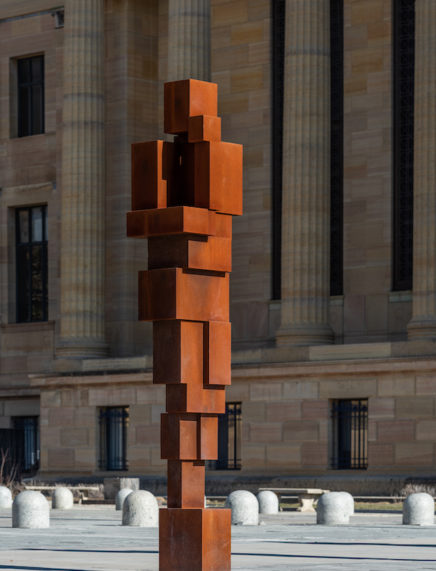

In 2014, the modern and contemporary art’s fair Art Basel partnered with Kickstarter to create The Crowdfunding Initiative, a platform which connects Art Basel’s audience to the contemporary art projects that need funding. These projects are selected by a jury of professionals and supported by non-profit arts associations and institutions. Along with Robert Irwin’s installation at the Chinati Foundation, William Kentridge’s first public art work was also selected. The South African artist’s mural, adorning the embankment walls of the Tiber River in Rome and titled Triumphs and Laments – A Project for Rome, was able to reach its target of $80,000 (approximately 70,000 Euros) nine days before the expected deadline and a month before the project’s opening. This 1,800-foot long and up to 30-feet high frieze depicts sixty mythological and historical roman icons, from antiquity to present, which form a procession of silhouettes going from Ponte Sisto to Ponte Mazzini. It will fade over time since the figures were created by power washing the walls over stencils created from the artist’s drawings. While funding for Irwin’s and Kentridge’s projects has now been secured thanks to large communication campaigns and the support of powerful private and public institutions, Sol LeWitt’s outdoor installation at the Kivik, a Swedish art center focusing on the connection between art and architecture, is still in need of public generosity. Each year, the Kivic Art Center, located in the south-east of the Skåne region on the Baltic Sea coast, opens a new pavilion. Each pavilion combines art and architecture and opens a dialogue with the amazing surrounding landscape. The center benefits from a strong local implantation and from the support of local industries. Since 2007, the Kivik Pavilions Project has thus completed seven installations-pavilions, among which one of the most famous stemmed from the collaboration between architect David Chipperfield and artist Antony Gormley (A Sculpture For The Subjective Experience Of Architecture, 2008). According to an article from Art Newspaper, LeWitt‘s 9 Towers was conceived shortly before his passing in 2007 and submitted to the Kivik Center by his close friend and American sculptor Jene Highstein. This 16-foot high sculpture consists in nearly four thousand white concrete blocks imported from the United States. Its completion, which was initially scheduled for the summer of 2014, has been postponed several times. On the Kivik website, a crowdfunding campaign allows people to donate one or several blocks of the sculpture for 17 Euros a piece. So far, 2659 blocks were sold. If completed, it will be the artist’s first monumental and permanent work of art installed in Scandinavia.

New Audiences

Not far from Paris, in Milly-la-Forêt, nestled in the forest of Fontainebleau, stands Le Cyclop, a monumental 74-foot high sculpture. Made of 350 tons of steel, it was mostly created from scraps (metal, wood, broken pieces of mirror and ceramics) between 1969 and 1994 by Jean Tinguely and Niki de Saint Phalle and in collaboration with other artists such as César, Arman, Jean-Pierre Raynaud, Larry Rivers, Jesus Rafael Soto and Daniel Spoerri.

Le Cyclop is a bodyless head, with a single eye scrutinizing its surroundings. Covered with thousands of scintillating mirror fragments which reflect the natural movement of the trees and clouds, Le Cyclop constantly interacts with the surrounding nature. Partially restored in 1996, its Face aux Miroirs deteriorated due to exposure to the elements, and it is now in urgent need of a major restoration. The piece was donated to the French government by Tinguely in 1987, and the French national center of fine arts (Cnap – Centre national des arts plastiques), which oversees the preservation of public collections, is looking for patrons to help cover part of the restoration costs, which are currently evaluated at 1.2 million Euros. Furthermore, the Cnap partnered with MyMajorCompany in order to raise 10,000 Euros online while giving more exposure to the artwork and to the importance of its restoration: reaching out to the public seemed to make sense to Aurélie Lesous, patronage, collaboration and mediation coordinator at the Cnap, because of the collaborative nature of Le Cyclop, which required the participation of numerous artists over a period of 25 years. Over 130 contributors have answered the call and donated nearly 15,000 Euros, which shows the public’s interest for this unique work of art. Companies like Saint-Gobain, Crédit Agricole d’Ile-de-France Mécénat and Fondation du Crédit Agricole-Pays de France have also committed to support the restoration, which still hasn’t started: Saint Gobain through financial and labor contributions, Crédit Agricole and le fonds de dotation Île de France through financial contributions for the restoration itself as well as for an educational program offering mirror trade high school students the opportunity to participate in the restoration. While awaiting the launch of this restoration, Le Cyclop remains accessible to the public and to schools, and a series of free exhibits, screenings, and conferences called “La Clairière des possibles” is programmed for November.

Although in some cases crowdfunding only accounts for a minor role in a complex network of financial ressources – public funds, corporate or private patronages, skills and technical patronages, etc. – it nonetheless participates to a communication strategy on a larger scale and on the longer term. It allows to promote the artwork and the project in a different way, to test its public appeal, to reach out to potential patrons beyond the campaign itself and to raise awareness among diverse audiences. In a recent article from the Mag de l’Admical, an association created in 1979 aiming at developing corporate patronage, Olivier Ibañez, consultant on patronage and partnerships at the Centre des Monuments Nationaux (CMN), explains the partnership between CMN and MyMajorCompany: “Increased exposure is the real benefit of this approach – particularly among a new, younger audience, who might be less familiar with these institutions which are looking to spruce up their image.” The goal is undeniably to raise money, but it is first and foremost to allow a young audience to gain ownership of its culture, to actively take part in it, and to hand over the very existence and preservation of this heritage to future generations.

In times of digital revolutions, of cultural budget cuts and of a collaborative economy which relies on community and social networks, artists, institutions and collectivities have found new financial and social tools as well as new audiences to help generate and preserve artistic projects. Outdoor works of art are just one example in a much larger movement, but they illustrate, as Guillaume Baudin explains, “a new relationship to an art form which is open and accessible to all and which contributes more widely to the promotion of contemporary practices.”