The Vostell Malpartida Museum

In the spring, the landscape of northern Spanish Extremadura is a display of warm greens and incandescent yellows, colors of holm oaks and broom plants, dotted with the milky hues of labdanum flowers peeking through vigorous foliage. But what truly stands out in this bucolic landscape is the imposing chaos of granite rocks piling up against the horizon, forming large, smooth platforms lined with heather and moss.

In Malpartida, near Cáceres, the presence of granite intensifies and the natural monument “Los Barruecos” offers an impressive experience to the senses. The piled-up rocks, the small but beautiful dam, the Iberian vegetation and the blue sky filled with storks that have settled here make up one of the most singular natural images of the Iberian peninsula. When facing such beauty, it is easy to understand why Wolf Vostell, major European artist of the second half of the 20th century, chose to build a museum here.

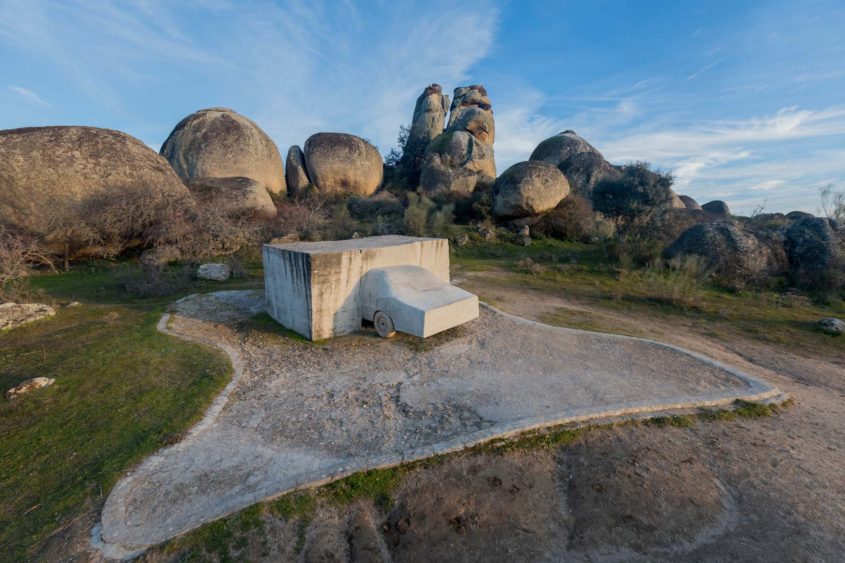

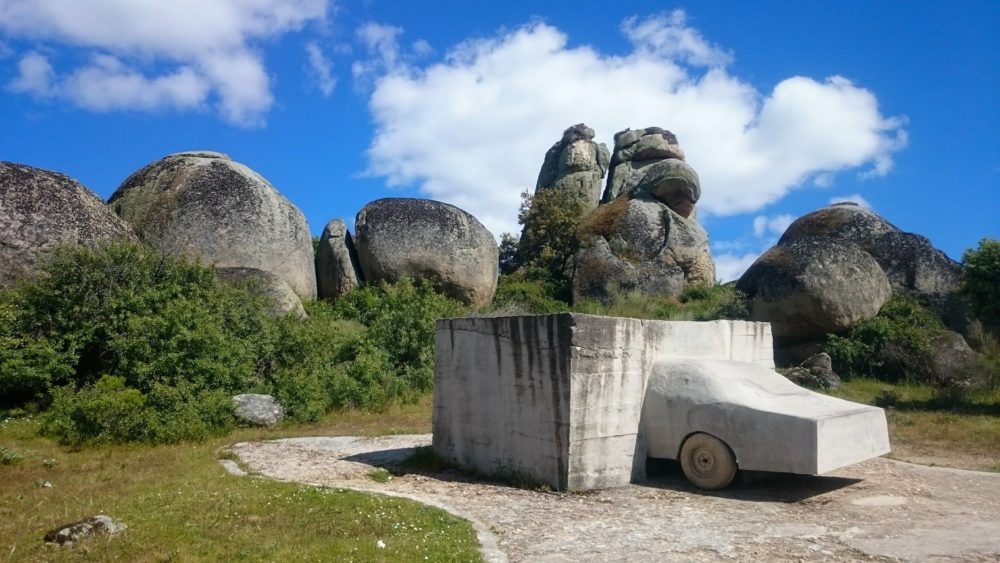

Certainly under the influence of his spouse Mercedes Guardado Olivenza, who was native to the region, Vostell discovered Extremadura at the end of the 1960s and referred to the granitic chaos as “a natural work of art”. The Vostell Malpartida Museum officially opened in 1976 with the inauguration of VOAEX (Viaje de (H)ormigón por la Alta Extremadura [Car in Concrete] – a concrete outdoor sculpture installed among the gigantic granite rocks.

The mass of VOAEX, in perfect harmony with that of the granite, mimics a car that is about to be swallowed by a heavy concrete block. The sense that an accident is about to happen is more than present. But the sculpture actually constitutes the synthesis of the artist’s concerns, and more specifically a certain incompatibility between nature and a rapidly growing modernity that progressively blinded human understanding. Vostell seems to be erecting the symbols of a modernity that goes hand in hand with metal, concrete, destruction, but also with machines and mechanical and technological developments. Metal and concrete are the structuring elements of a sterile and inorganic modernity, with which the artist works in an optimistic desire to transform while always reminding humanity’s harmful potential.

Inside the museum, beyond the gates designed by Vostell, other works underline these tensions: environments mechanized by technology lead the audience to take a critical look on modern progress; cars, motorbikes and televisions prefigure modernity in its self-destructing splendor and become a means of expression that allows Vostell to reflect on life’s contemporary and transitory aspects, on its mutability and its fluidity; large paintings come out of the canvas to sculpt death and decomposition. Some of his works are particularly interesting: those that were born from a technique he invented, Dé-collage – where art is simultaneously produced through construction and deconstruction – and installations – particularly La fiebre del automóvil [Car Fever] (1973) and El fin de Parzival [The End of Parzival] (1988), imagined by Salvador Dalí in the 1920s and materialized by Vostell decades later.

If the works inside the museum are undeniable testimonies of Wolf Vostell’s genius, it is also evident that it is outside that the great concepts that the artist tries to combine are more present. Art, life and nature are fully materialized around the museum. To all this, comes added Vostell’s desire to gather and host other artists from around the world in such a special site, a place for them to create artworks and performances.

With this in mind, not far from VOAEX, El muerto que tiene sed [The Thirsty Dead Man] (1978) plays with a discretion that is far from being devoid of defiance: a metallic cylinder, painted in black, the circular base of which is lined with a series of plates. The concept is hermetic, just like the shape of the sculpture. A more thorough research reveals that, in reality, this cylinder is a gigantic container of thoughts. In 1978, the year of the inauguration, a hole in the cylinder allowed the audience to slip their head inside and reflect on the nature of the artwork. The hole was later sealed, and will only be reopened 5000 years after the date of installation. Only then will the thoughts that were locked inside be released. The meaning of the plates remains to be explained – maybe the announcement of a banquet; a table about to collapse under the force of gravity and smash to pieces onto the hard granite; a reference to the void, hunger and thirst that follow death and to the illusory needs that we encounter through life?

Inside the museum, ¿Por qué el proceso entre Pilatos y Jesús duró sólo dos minutos? [Why Did the Trial Between Pilatus and Jesus Only Last Two Minutes?] (1996-1997) looks like a totemic monument made of cars (again cars), pianos, a Russian military plane and old computers and monitors. An ancient computer is placed onto a car, which follows the plane that seems to pierce the car and stands in a precarious balance on one of the pianos that seem to be playing the gloomy melody of destruction. Indifferent to all this, storks have decided to build their nests here, thus offering their unique reading of the work. In the end, nature always finds a way.

This duality made of movement and immobility, organic and inorganic, animal and mineral, is also visible in Toros de Hormigón [Concrete Bulls] (1989-1990), where Vostell joins two distinct chronologies by referring to Toros de Guisando [Bulls of Guisando] – pre-Roman sculptures located in Spain and consisting of bulls carved in massive blocks of granite. Interpretations are multiple, depending on the possible references that come to the visitor’s mind: transhumance, the cleavage between tradition and modernity, death, or, other possibility, the adoration of ancestral practices rooted in local economic activities, the relationship to Picasso’s Bull’s Head (1942) and the potential of the found object, already precursor of conceptualism, etc.

Two other outdoor works show the museum’s artistic inclination to experimental movements such as Fluxus, conceptualism or happenings. In Painting to Hammer a Nail/Cross Version (2000), Yoko Ono invites visitors to conceive the artistic object themselves. In this work born from an initial experience with Painting to Hammer a Nail (1961), the artist transforms the action and the gesture into art, suggesting a reflection, an introspection on humanity’s great symbols and on the ambivalences they create. In this context, the crosses are riddled with nails, the result of a somewhat obscure performative experience. Raphaël Opstaele, on the other hand, offers a more soothing and contemplative moment with Templo del Viento [Wind Temple] (1983-2012), a series of hollow bamboo sticks that sing to the wind and drafts, a sound associated with the ever improvised song of the surrounding nature.

We left the Vostell Malpartida Museum with the feeling that it remains one of the most interesting experiences in contemporary museology and a true cultural center featuring artworks that hold a message and a concept that are still relevant today. And despite its remote location, the museum has undeniably been fundamental to the development of European contemporary art and a meeting point for artists from around the globe.

The Vostell Malpartida Museum

Tickets: €3.

From March 21st to September 20th – 9:30am to 1:30pm and 5pm to 8pm. From September 21st to March 20th – 9:30am to 1:30pm and 4pm to 6:30pm. Sundays – 9:30am to 2:30pm

The Vostell Malpartida Museum includes three collections (Wolf e Mercedes Vostell, Fluxus – Donation Gino Di Maggio, and Artistes conceptuels) and is located in a former 18th century wool washhouse. A more modest museological center retraces the entire history of the region’s economic, social and cultural activities.

Other attractions in Cáceres: Cáceres is one of Extremadura’s biggest cities and benefits from a rich historical center and many points of interests and tours. The visual arts center Fundación Helga de Alvear is a must-see and holds an impressive minimalist art exhibition belonging to the Helga de Alvear collection.