Between dread and delight, the aesthetics of the sublime

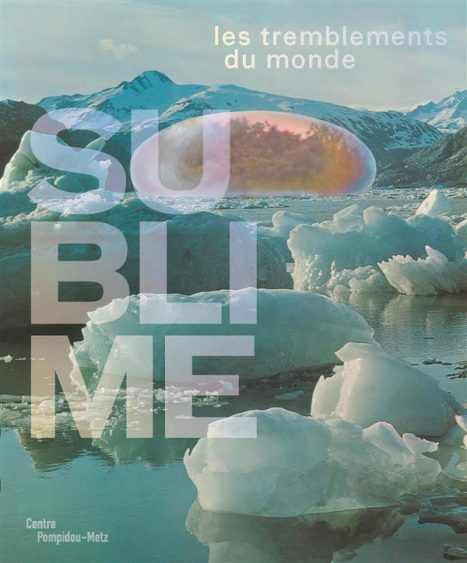

“My body is made of the same flesh as the world’s.” Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s sentence resonates particularly well with the exhibition “Sublime, les tremblements du monde”, currently at the Centre Pompidou-Metz and beautifully supplemented by this catalogue. For it is, indeed, all about the relationship between humans and nature, about how they look at it, apprehend it, alienate it or embrace it.

This exhibition echoes nature’s recent furies and humans’ technical failures: earthquakes and tsunamis in Indonesia and Japan, hurricane Katrina in the United States, nuclear disaster in Chernobyl, to name just a few. We witnessed these events, filled with dread, and yet somewhat fascinated by nature’s power and the force of their aesthetic forms.

To help us understand and consider, among other things, the climatic challenges which are ahead of us and our ambivalent take on those disasters, the exhibition revisits, through art history, Edmund Burke’s XVIIIth notion of the “Sublime”, which defines our feeling of smallness against nature’s immensity. “Les tremblements du monde” (“The tremors of the world”) are ambiguously fascinating, altogether terrifying, repulsive, and moving. Using a diversity of media, three hundred works by both ancient and contemporary artists illustrate the experience of humans and artists facing nature, and try to question observers on their relationship to the environment.

The genealogy of our rapport to the Sublime starts with the representation of a grandiose, tormented nature, with storms and volcanoes, by artists such as Turner, Friedrich, Missika or Allouche… This overwhelming nature also takes the form of imaginary disasters in the works of Robert Smithson, Lars von Trier, Leonardo Da Vinci or Cornelia Parker… and intensifies with the “invisible” disaster entailed by men’s domination of nature, with artists such as Darren Almond, Barbara Leisgen, Robert Adams… Nature remains overwhelming but is now overtaken by humankind. In this new context, artists start looking at things differently. They become more engaged, and create answers. For some, such as Juan Navarro Baldeweg, Klaus Pinter or Jacques Rougerie, the answers are utopian, involving architectural alternatives aimed at protecting life… For others, such as Gina Pane, Ana Mendieta, Agnes Denes, the answers consist in a series of protective, nurturing, regenerating and transformative gestures towards the landscape… Finally, Tadashi Kawamata finds his answer through remembrance, and his installation “Under the water”, dedicated to the victims in Japan, questions the observer’s memory.

Thanks to visual and reflective documentation, this catalogue accurately illustrates the evolution of the notion of the Sublime throughout the centuries. It contains five long introductions by different contributors which set the main frames of the exhibition: “Chaosmos”, by Hélène Guenin, “Sublime et cosmos, du romantisme à l’art contemporain”, by Olivier Schefer, “De l’imaginaire fossile au cours du pétrole”, by Hélène Meisel, “Land art et écologie”, by Serge Paul, and “L’anthropocène et l’esthétique du sublime”, by Jean-Baptiste Fressoz. These large chapters are followed by a chronological approach of nature’s representation: La nature trop loin, imaginaires de la catastrophe, la tragédie du paysage, alternatives, réenchantement. All these texts beautifully serve the works and artists presented here thanks to reproductions of different sizes, often in full page. Each work and each artist is meticulously documented and placed in the context of the exhibition. The catalogue concludes with artists who have a more serene view of our sentiments towards nature. They all, through their work, become creators of the Sublime.

Sublime, les tremblements du monde, Hélène Guenin, Centre Pompidou-Metz catalogue exhibition, 11 february – 5 septembre 2016, 223p, Centre Pompidou-Metz Editions, 2016.